Detroit Entrepreneur Builds Eco-Conscious Candle Brand

Unique Monique Scented Candles, a Detroit-based business founded by Monique Bounds., aims to produce candles and household products with clean ingredients and local supply chains. What began as a personal hobby during college has evolved into a full-time venture producing coconut oil and soy-based candles made with essential oils and locally sourced materials. SBN Detroit interviewed Bounds about launching a sustainable product line, sourcing challenges in Michigan, and how small manufacturers are navigating the growing demand for eco-conscious home goods. Q: Tell us how Unique Monique began and what motivated you to turn candle-making into a business. A: I started making candles about five or six years ago. It began as a hobby – something calming and creative that helped me manage stress while balancing college classes I was taking and work. I shared them with friends and family, and the response was positive. As I continued experimenting, I began taking business mentoring classes. My mentor helped me understand how to turn my hobby into a business, including forming my LLC and developing relationships with local stores. That’s when I realized there was real potential to grow this into something sustainable. Over time, I also became more intentional about ingredients. I noticed some of the natural components I was using felt better for people in my own household, especially those with allergies or respiratory sensitivities. That shaped the direction of the brand. Q: What distinguishes your candles from traditional scented candles on the market? A: The foundation of my candles is soy flakes derived from soybeans and coconut oil, blended with pure essential oils. I avoid harsh chemicals and synthetic additives. The goal is to create a cleaner burn with minimal soot and no heavy chemical residue. For me, sustainability starts with setting non-negotiable ingredient standards. I use boiled wax methods, essential oils, and thicker glass jars to prevent cracking and extend product life. Packaging also matters. I try to use materials that are safe and environmentally responsible. Q: From your perspective, what does building a genuinely eco-conscious product require beyond just ingredients? A: It requires discipline. Sustainability isn’t something you add later, it has to be built into your foundation. That means being selective about suppliers, understanding where materials come from, and balancing cost with integrity. Many ingredients are processed in ways that aren’t obvious at first glance, so sourcing responsibly takes research. I’ve also had certain ingredients lab tested to ensure they align with my standards. Beyond ingredients, packaging, waste reduction and long-term product use all matter. I think about how the product lives in someone’s home and what happens after it’s finished. Q: How are consumer attitudes around indoor air quality and “clean” products evolving? A: Consumers are more informed now. People ask questions about what’s in their products. They want to know about essential oils, wax types, and where ingredients come from. There’s more awareness around chemical exposure in everyday products. At the same time, there are misconceptions. For example, some people have concerns about soy wax because of misinformation online. Education is important – not everything labeled “natural” is automatically good or bad. It’s about understanding the sourcing and processing behind it. Q: You also emphasize sourcing locally. Why is that important to you? A: Whenever possible, I source ingredients locally in Michigan. I want to keep money circulating within the state and reduce transportation impact. Local sourcing helps minimize carbon footprint and supports other small businesses. It does require careful vetting. But I believe strengthening local supply chains is part of long-term sustainability. Q: How has community engagement played a role in your growth? A: Community events have been very important. I’ve participated in local showcases like the Henry Ford Museum during Black History Month, as well as events connected to the NFL Draft and the Detroit Grand Prix. These events create opportunities not only to sell products but to educate consumers about clean ingredients and sustainable manufacturing. Being present in the community has helped build awareness. Q: Beyond candles, are you expanding into other product categories? A: Yes. I recently launched an antibacterial laundry detergent made with biodegradable, plant-based ingredients. It’s currently carried by More Herbs, a local health and wellness store. I’m also exploring home cleaning kits, and other self-care products. The long-term vision is to build a marketplace that supports other small businesses with similar sustainability values. Q: Looking ahead, what does growth look like for Unique Monique? A: Right now, most of the business is online, but I do have a physical office location. I’d like to expand retail partnerships and possibly open a brick-and-mortar space in the future. Workshops and classes are another goal… teaching others about candle-making and sustainable product development. Ultimately, I want every decision the company makes to support healthier homes, stronger communities and a cleaner environment. Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on sustainable business practices in and around Detroit.

Building More Sustainable Homes Through Automation

Citizen Robotics is a Detroit-based nonprofit that advances the use of robotics and digital manufacturing in residential construction, focusing on improving productivity, sustainability, and long-term affordability. Best known for its early work in 3D-printed housing, it explores how alternative construction methods and new financial models can reduce material waste, lower lifetime operating costs, and enhance the resilience of homes. SBN Detroit interviewed Tom Woodman, founder and president of Citizen Robotics, about why housing has lagged behind other industries in adopting new technologies, the structural barriers facing innovative construction methods, and what it would take for models like 3D-printed housing to move from experimentation to scale. Q: Tell me about Citizen Robotics and the impetus behind it. A: The homebuilding industry largely missed the digital revolution. Productivity has been flat for decades and, that has directly contributed to the rising cost of new construction. It has also limited progress on sustainability, from material efficiency to energy performance. At the same time, the industry has struggled to attract younger workers, in part because it’s perceived as manual and outdated. Citizen Robotics was formed in response to that dynamic. The idea was to demonstrate that a robotic future for homebuilding is not only possible, but achievable now. We centered our early work on 3D construction printing because it brings together robotics, digital design, and material innovation in a way that could fundamentally change how homes are built. Q: Citizen Robotics drew early attention for its work in 3D-printed housing. Where is the organization today? A: That early work generated a lot of interest from the community and the media. One of the most important outcomes was that people could physically experience the technology. Thousands of people toured the house, touched it, walked through it, and asked questions. You could see perceptions shift once people understood what was actually possible. Today, we’re working more directly with municipalities and partners to move toward a structure that can support real-world deployment. We’re exploring a for-profit framework that would allow 3D printing to achieve broader impact, including a model we call “Build for Equity,” which combines rental housing with shared equity over time. Q: In your experience, what are the biggest barriers to scaling new housing technologies like 3D printing? A: Many people assume the barrier is more innovation — better robots, better materials. In reality, we’ve shown that even existing robotic systems can deliver meaningful gains, not only in productivity but in material efficiency and long-term performance. The real barriers fall into four areas: market acceptance, continuity of capital, industry conservatism, and a funding gap around productivity. Housing is expensive no matter how it’s built, and resale value is always top of mind. Anything outside the mainstream creates anxiety for buyers, lenders, and developers. Sustainability benefits, such as durability, resilience, and lower operating costs, are rarely reflected in how homes are valued or financed, which makes adoption harder. There’s also a Catch-22. To make homes cheaper, you need volume and repetition. But to get volume, you need lenders to underwrite projects, and they need comparable data that doesn’t yet exist. Q: Why has housing been so slow to adopt automation compared to other industries? A: A big part of it comes down to incentives. Construction largely delivers what the system pays for. The way homes are financed, maintained, and insured often works against affordability over the long term. If we want healthier, more durable homes, we need to reward innovation rather than cost-cutting that degrades quality. Right now, the system works well for those already positioned to profit from it. Changing outcomes requires changing incentives. Q: From your vantage point, where is the greatest opportunity to rethink how homes are built? A: One of the biggest opportunities is Detroit’s inventory of residential lots, combined with a different financial model paired with industrialized construction methods. Build for Equity is about constructing homes for rent while allowing renters to build equity over time through a shared fund structure. That model allows us to focus on the total cost of ownership. From a sustainability standpoint, materials like concrete offer fire, flood, and storm resilience, along with lower long-term maintenance and operating costs. When homes are evaluated based on total cost of ownership — including energy use and durability — innovation becomes much easier to justify. Q: What does it take to keep an innovation-focused organization viable during periods of uncertainty? A: It’s difficult, particularly in a challenging fundraising environment. But the need hasn’t gone away. Around the world, 3D construction printing is advancing – in Texas, Florida, Ontario, Kenya, Japan, and beyond. We learn from those efforts and adapt what makes sense locally. The key is securing capital for repeatable projects so the technology can move beyond prototypes and generate the data lenders need. Q: What would meaningful progress look like for Citizen Robotics over the next few years? A: Moving from prototypes to a repeatable playbook that lenders are comfortable underwriting. Training and placing at least 60 workers into high-tech construction roles. Scaling projects across multiple municipalities. Michigan has the ingredients to become a proving ground for innovative and more sustainable construction, from advanced manufacturing expertise to policy interest in sustainability. The challenge is unlocking the first wave of projects. Q: What needs to change for innovative housing models to become permanent? A: We need financing structures that optimize for total cost of ownership, not just upfront cost. Philanthropy can play a role in de-risking early projects and funding workforce development. Policy matters too. Zoning reform, incentives for net-zero housing, and support for local job creation all help create space for innovation. With the right mix of public, private, and philanthropic investment, we can keep jobs local, improve housing quality, and move toward a more sustainable construction system. Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on sustainable business practices in and around Detroit.

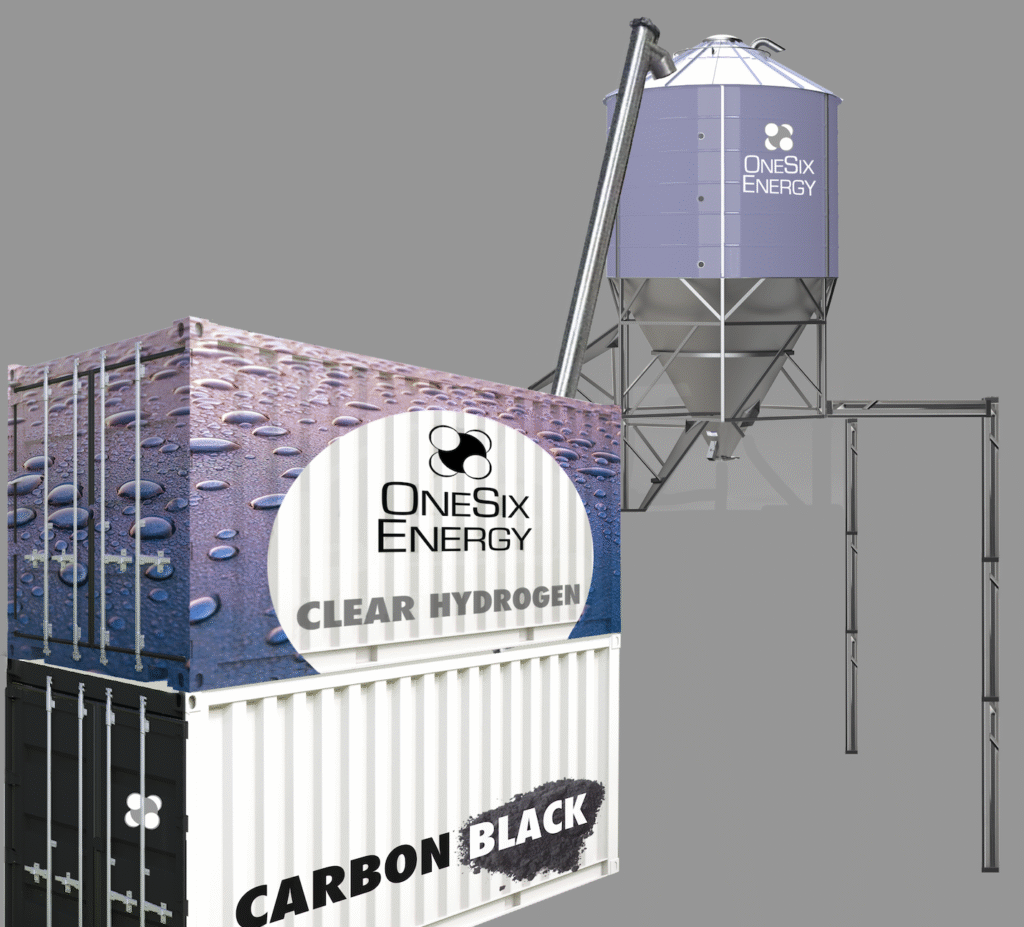

Rethinking Hydrogen Production

Detroit-based OneSix Energy is a clean-energy technology company focused on advancing a lower-carbon approach to hydrogen production. Headquartered at Newlab in Detroit, the startup is developing a proprietary methane pyrolysis system designed to produce hydrogen without carbon dioxide emissions, while also generating solid carbon as a co-product. SBN Detroit interviewed with cofounder Stefan Sysko about the company’s origins, its approach to hydrogen production, and why Detroit is positioned to play a leading role in the next phase of the energy transition. Q: Can you give us the elevator version of OneSix Energy — how it got started, the impetus behind it, and the approach you’re taking to hydrogen production? A: OneSix Energy really began with my co-founder, Dan Darga, who back in 2002 was working at General Motors. He read about the hydrogen economy and immediately knew he wanted to be part of it. He transferred to GM’s fuel cell division in upstate New York, then later worked for a solid oxide fuel cell company. While there, he kept running into the same problem: carbon buildup clogging systems. His perspective was that we were fighting nature instead of working with it. That led him to start thinking differently about surfaces, materials, and how carbon behaves. Dan eventually left to work at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he learned how to take ideas from concept to deployment in extreme, real-world conditions. He combined these two experiences, refined them, and approached me. I’ve been a lifelong entrepreneur, and I felt I had one more startup in me — one that could genuinely address a major global challenge. We incorporated OneSix Energy nearly two years ago, bootstrapped the initial design and modeling, filed a patent that’s now pending, raised a friends-and-family round, built and independently tested a prototype, and are now moving toward a pilot phase. Q: What problem is hydrogen uniquely positioned to solve that other energy carriers can’t? A: Hydrogen is incredibly energy-dense by mass, and when it’s used, the only byproduct is water vapor. It’s versatile — it can be used as a fuel for power generation or as a chemical feedstock. Hydrogen has been called “the fuel of the future” for decades but it’s difficult and expensive to produce cleanly. Today, about 90 percent of hydrogen is made using steam methane reformation, which is cheap but very dirty — roughly 11 tons of CO₂ for every ton of hydrogen produced. Electrolysis, on the other hand, is clean but extremely expensive and water-intensive. It requires fresh water, significant electricity, and even when powered by renewables, you lose about half the energy in the process. When you look at sectors like data centers — which already consume enormous amounts of electricity and water — electrolysis actually worsens the problem. Our system is different. We’re off-grid. We recirculate a fraction of the hydrogen we produce to power our reactor, so we don’t need external energy, and we don’t use water. In fact, we generate fresh water as a byproduct. Q: Can you explain methane pyrolysis and what OneSix Energy has developed? A: Methane pyrolysis involves taking methane — CH₄, the main component of natural gas — and breaking it into hydrogen and carbon using high temperatures in the absence of oxygen. Because there’s no oxygen, you don’t form CO₂. Instead, you produce solid carbon. That solid carbon – or “carbon black” – is actually valuable. It’s used in products like tires, shoe soles, and industrial materials. There’s a roughly $40 billion global market for carbon black today. Our goal is to upcycle that carbon while producing hydrogen at a lower cost than electrolysis, without water use or external energy input. Q: Hydrogen production often involves trade-offs. What innovations are helping overcome those barriers? A: Right now, the industry is stuck between options that are either cheap and dirty or clean and expensive. What’s changing is the recognition that we need new pathways — not just incremental improvements. Innovations in materials science, reactor design, and system efficiency are making approaches like methane pyrolysis viable at scale. The key is eliminating emissions without introducing new resource constraints. Q: Where do you see the earliest and most impactful applications for clean hydrogen? A: Two areas stand out immediately: data centers and shipping ports. Ports face increasing regulatory pressure because of emissions from ships idling while docked. Hydrogen-powered equipment and shore power could significantly reduce pollution while keeping operations moving. We also see opportunities in power generation for buildings, factories, and industrial facilities. Long-term, hydrogen fuel for heavy-duty transportation — Class 8 trucks, for example — is very compelling. Electrifying those vehicles requires massive and expensive batteries that reduce payload capacity. Hydrogen avoids that issue. Q: Why build a clean-energy technology company in Detroit? A: Detroit put the world on wheels. There’s no reason it shouldn’t lead the energy transformation. We’re at Newlab, surrounded by engineers, manufacturers, and people who understand how to scale physical systems. Detroit is a perfect microcosm — a place where you could demonstrate how an entire city transitions to clean energy. Plus, I was born and raised in the city, so it’s home to me. Q: What misconceptions do you encounter most often about hydrogen? A: The first is safety. People immediately think of the Hindenburg. But hydrogen is actually lighter than air and dissipates quickly, whereas gasoline fumes stay low and linger. When you look at safety data, hydrogen performs very well compared to other fuels. The Hindenburg taught us the hard way that we need to develop unique handling procedures for hydrogen – and we have. Q: What should Michiganders understand about hydrogen’s role in a sustainable energy future? A: Michigan potentially has significant natural hydrogen resources, which should be explored. But we need to remember that it will likely be years, if not decades, before that becomes viable, We also have the Great Lakes — which must be protected. If all hydrogen today were produced via electrolysis, the water consumed would be equivalent to Lake St. Clair

Inside Michigan’s Environmental Justice Landscape

Regina Strong serves as Michigan’s first Environmental Justice Public Advocate, leading the state’s Office of the Environmental Justice Public Advocate. Her role focuses on addressing environmental justice concerns raised by communities, helping residents navigate environmental systems, and working across state agencies to improve equity in environmental decision-making. SBN Detroit interviewed Strong about the challenges communities are facing across Michigan and what environmental justice work looks like in practice. Q: As Environmental Justice Public Advocate, what does your work look like day to day? A: There really is no typical day. This role was created to address environmental justice concerns and complaints, to advocate for equity, and to help communities navigate systems that can feel opaque or inaccessible. That can mean many things. On a given day, I might be working on our Environmental Justice Screening Tool as we migrate it to a new platform, meeting with one of our 43 grantees across the state, or sitting down with other state departments or divisions within EGLE, where my office is housed. Other days are spent directly with community members – listening to concerns, helping them understand what levers exist, and figuring out how to move forward. The work ebbs and flows depending on what’s happening in communities. Over the past seven years, we’ve seen some issues emerge seasonally, in response to new development, extreme weather, or long-standing infrastructure issues. Ultimately, my work is deeply relational and constantly evolving. Q: What are the most pressing environmental justice issues you’re hearing across Michigan and how do they differ between urban, suburban, and rural communities? A: There’s actually a lot of overlap across geographies. Whether people live in dense urban neighborhoods, suburban communities, or rural areas, we consistently hear concerns about water – lead service lines, contaminated wells in rural areas, and flooding. Air quality is another major issue, especially near industrial corridors or transportation infrastructure. In more densely populated areas, concerns often cluster around industry, waste facilities, landfills, and cumulative air pollution. In rural areas, it may be wells, septic systems, or access to clean drinking water. Across all regions, energy burden comes up frequently, particularly during winter months, when households are forced to spend a disproportionate share of income on utilities. Climate change is amplifying many of these issues. Flooding, power outages, and extreme weather events are becoming more common, and their impacts are not evenly distributed. The underlying issues may differ by location, but the throughline is vulnerability tied to infrastructure, income, and exposure. Q: What are the hardest gaps to close when translating community concerns into action? A: One of the biggest challenges is that environmental justice issues rarely fall under a single authority. A concern may involve state permitting, local zoning, county health departments, and federal regulations all at once. Our office often helps communities navigate those layers. From an environmental justice perspective, equitable access to decision-making is critical. We work to ensure voices are heard, especially in communities that have historically been underserved. We do a lot of resilience planning in – for example – the 48217 ZIP code (Southwest Detroit) in the heart of a very dense industrial corridor. We also work with communities near hazardous waste facilities and communities with drinking water concerns. Many of these challenges have deep historical roots. Our role is often about helping communities access resources, understand processes, and advocate effectively while acknowledging that solutions are rarely immediate, yet possible. Q: To that end, how does history complicate environmental justice work today? A: History matters a great deal. Many environmental regulations around air and water are set at the federal level and applied category by category. Communities, however, experience impacts cumulatively – air, water, land use, and health intersecting in daily life. That mismatch creates tension. Residents want holistic solutions, but regulatory frameworks don’t always account for cumulative impacts. Before the Clean Air Act and Safe Drinking Water Act, people lived near industrial facilities for decades – and still do. Laws have improved, but legacy exposure and infrastructure decisions remain. Balancing regulatory constraints with community realities is one of the most complex aspects of this work. Q: What structural or systemic barriers are hardest to change? A: Policy is often written within narrow frameworks that don’t always center people’s lived experiences. That’s a persistent barrier. Another is data – how it’s collected, interpreted, and applied. MI EJ Screen, the state’s environmental justice screening tool is designed to help address that gap. It looks at environmental conditions, demographics, and health indicators together, creating a shared reference point for communities, government, and industry. The first version was launched in 2024, and expanding its usability is a priority because shared data helps align conversations and advocacy. Understanding how existing laws interact and where they fall short remains both a challenge and an opportunity. Q: How has your background in clean energy advocacy and community development shaped your approach? A: Where you live often determines the challenges you face. Working in community development and later in clean energy made that clear. Lower-income communities and communities of color are more likely to experience environmental burdens, often due to proximity to industry or aging infrastructure. That perspective informs everything I do. Some issues can be addressed through regulation, but others require working directly with communities to improve daily quality of life. Our Environmental Justice Impact Grant Program is one example – 43 grants statewide, including many in Detroit, supporting grassroots organizations, schools and communities addressing local concerns. This office sits outside of regulatory enforcement, which allows us to take a broader, more human-centered view. Q: How do you think about progress for residents living with impacts right now? A: Progress can look small but be very meaningful. Having a dedicated office focused on environmental justice is progress. Having tools that didn’t exist before is progress. If progress means a senior is no longer dealing with basement flooding because they received support for a sump pump, that matters. We have to focus on both micro-level quality-of-life improvements and

Navigating Environmental Compliance

Butzel is one of Michigan’s longest-standing law firms, advising businesses across industries on regulatory compliance, environmental law, and complex commercial matters. As environmental expectations evolve alongside shifting regulatory realities, the firm plays a key role in helping companies navigate both legacy challenges and emerging risks. SBN Detroit interviewed Butzel shareholder Beth Gotthelf to discuss how environmental compliance, sustainability, and innovation are intersecting today — particularly in Southeast Michigan — and what businesses should be paying attention to in the years ahead. Q: From your perspective, what are the most consequential changes shaping how companies approach compliance and sustainability today? A: Many companies still treat compliance and sustainability as separate conversations. Compliance is something they aim for while sustainability is framed as an aspirational goal. Where those two intersect most often is when sustainability also makes business sense. Reducing water use, reusing materials, and improving efficiency often lower costs. Recycling and waste reduction can improve margins. As a result, many organizations are approaching sustainability less as a branding exercise and more as a fiscal and operational strategy. Q: How are businesses navigating the tension between accelerating sustainability goals and increasingly complex regulatory frameworks at the state and federal levels? A: Right now, I don’t see the same level of tension that existed a year or two ago, particularly in Michigan, unless they also have facilities outside of the U.S. or in California. Many companies still believe in climate action and sustainability, but they’re not always using that language domestically given the current federal environment. That said, sustainability reporting is mandated outside the US, with the European Union leading the way for larger firms, and nations like Australia, China, India, and Japan requiring disclosures. Those requirements still apply across all divisions, including U.S. facilities. One area where regulatory complexity is very real is battery recycling, particularly lithium batteries. The regulatory framework in the U.S. makes recycling more difficult than in other countries. That’s an area where we need better alignment to compete in the global market. There is progress happening, but it remains a challenge. Q: Southeast Michigan has a deep industrial legacy alongside growing environmental expectations. What challenges does that history create for remediation and compliance in this region? A: There are many. One challenge, for example, is that materials historically considered “clean fill” may no longer be viewed that way under current standards. The question becomes: do we excavate and remove it all? That creates dust for the area, truck traffic, emissions, road wear, and additional environmental impacts. In some cases, the net environmental benefit is questionable. We also face decisions around highly contaminated sites — whether to cap and manage contamination in place or attempt full remediation to pre-industrial conditions, which can be extremely costly and disruptive. I have simplified the issue but there is a balance between the desire to re-use contaminated sites (brownfield), finding a new productive use, and moving to a ‘greenfield,’ where you do not have to incur the cost, time, and worry of a brownfield. On the compliance side, Southeast Michigan has dense industrial areas adjacent to residential neighborhoods, particularly in places like Southwest Detroit. That proximity creates ongoing tension between maintaining industrial activity and protecting air quality and public health. These are not simple issues, and they require balance rather than absolutes. Q: Are you seeing a shift from reactive environmental compliance to more proactive strategies? A: Yes, overall companies are more proactive than they were decades ago. There’s greater environmental stewardship and awareness. There are better tools to allow for reuse, recycling, lower emissions, fewer chemicals being discharged in wastewater, better management of stormwater, etc. Companies are constantly looking and then implementing those tools. People, whether a resident, employee, or both–want products that last, clean water for swimming and boating, and healthy ecosystems — and they also want manufacturing and economic growth. Balancing those priorities is ongoing but can be done. We can build manufacturing and provide jobs while protecting the environment. Larger companies tend to have more resources to implement sustainability strategies and work with suppliers to raise standards. That said, the last year has been different. Incentives to pursue sustainability have diminished, and in some cases, companies feel penalized for investing in these efforts. That has slowed momentum for some organizations. Q: What role does innovation play in helping companies meet environmental obligations without stalling growth? A: Innovation is essential. It shows up in many forms — energy management software, automation, detection systems, improved chemicals, safer materials, and better protective equipment to name a few. There’s also a real opportunity to expand access to innovation, especially for small and midsize companies. More forums, education, and exposure to tools like energy tracking, water reuse, stormwater management, and greywater systems would help accelerate adoption. Innovation should be encouraged, not siloed. Q: How are climate-related risks influencing environmental decision-making in the Great Lakes region? A: Water quality has become a major concern. The Flint water crisis highlighted how municipal systems directly affect not just residential, but industrial operations. Poor water quality can damage equipment and disrupt production, forcing companies to install additional filtration and safeguards. Flooding is another growing issue. We’re seeing more frequent and severe rain events, impacting facilities across urban and rural areas alike. It is not good when a facility is flooded, potentially allowing chemicals to flow into the environment or causing work to stop. There are a variety of causes of flooding, some related to the drainage system on property, and some off property. Managing flood risk increasingly requires coordination between municipalities and private operators. Extreme weather — snow, wind, heat, flooding — is becoming part of long-term planning. Some larger companies are building redundancy across regions, but many Michigan businesses are smaller and must do the best they can within limited resources. Q: Compared to other regions, what opportunities does Southeast Michigan offer for sustainable redevelopment and clean manufacturing? A: Southeast Michigan has an abundance of industrial sites suitable for adaptive reuse, along with a strong workforce

Building a Circular Future

In the manufacturing world, sustainability is increasingly defined not just by recycling, but by what kind of recycling. For PolyFlex Products, based in Farmington Hills and part of Nefab Group, the future lies in creating closed-loop systems where materials are reused for equal or higher-value purposes — not simply “downcycled” into lower-grade goods. PolyFlex, which designs and manufactures reusable packaging and material handling solutions for the automotive and industrial sectors, is investing in circularity across its operations. The company’s goal is to ensure that plastics and packaging materials stay in circulation longer, retain value at end-of-life, and contribute to a more resilient supply chain. SBN Detroit interviewed Director of Sustainability Richard Demko, about the shift from downcycling to true circularity, the technical and cultural changes required, and what this evolution could mean for Michigan’s workforce and manufacturing economy. Q: What does “recycling for equivalent or higher use” actually look like in practice — and why is moving away from downcycling so important? A: Circularity, at its core, means manufacturing, recovering, and returning materials at end-of-life back into feedstock form to create something new. It’s about closing the loop — but we have to start with the basics: improving capture rates and diverting more material from landfills. The challenge is that recovery alone doesn’t guarantee success. One of the biggest barriers we face is the lack of demand for recycled feedstock. You can pour your heart into developing a fantastic recycling process, but if there’s no market for that material, the effort falls short. That’s why we need collaborative extended producer responsibility (EPR) systems that stabilize demand and make recycled regrind valuable, instead of punitive frameworks that simply point fingers. No single stakeholder can shoulder all the responsibility for circularity. It’s an ecosystem. Downcycling, meanwhile, is more like an off-ramp — it keeps materials out of landfills for a time but doesn’t truly close the loop. The goal is to return materials to their highest possible value so they can re-enter the economy at an equivalent or higher use. Q: In automotive supply chains, what opportunities do you see for keeping plastics and industrial packaging materials in circulation longer? A: Analyzing packaging fleets at the component level and asking what can be reused, what needs to be redesigned, and what truly has reached end-of-life is a great place to start. Pallets and lids are good examples. Often, those parts can be redeployed across multiple programs if you plan for it upfront. Traditionally, packaging was treated as disposable — once a product launched, everything associated with it ended up scrapped. Now we’re seeing a paradigm shift. Companies are designing for recyclability and reusability from the start. Some are even creating universal packaging platforms that can be shared across product lines. I like to say that carbon has become a kind of currency. When companies invest in reusable packaging, the return isn’t always measured dollar-for-dollar — it’s measured in carbon reduction. Those gains directly support broader sustainability goals, and, in some cases, they even help manufacturers comply with regulations that exempt circular packaging streams from waste classifications. At PolyFlex, we’ve already helped our customers divert several million pounds of plastic from landfills simply by applying design-for-recyclability principles and re-use strategies. It’s a shift toward smarter design — and it’s happening fast. Q: What are the biggest technical challenges in turning used materials back into high-value products — and where is the industry making progress? A: The biggest technical hurdle is consistency. Regrind blends vary depending on their source, and that variability can affect performance. The key is to manage it intentionally — introduce recycled feedstocks in small increments, fine-tune the process, and ramp up gradually. On the positive side, both equipment and operators are getting smarter. We’re seeing tremendous innovation in process technology that allows manufacturers to work with higher recycled content without sacrificing quality or throughput. Q: How do you design a product from the beginning with its second or third life in mind? A: It starts with identifying components that can become standards — like pallet dimensions or lid configurations that can be used across multiple applications. The more we can standardize, the more opportunities we create for re-use. It also requires a macro mindset. Instead of thinking in one product lifecycle, you think in systems. If you’re shipping a component from Detroit to Arizona, ask what can be sent back in that same flow. Can the packaging be refilled, reused, or repurposed? That kind of circular thinking transforms how supply chains operate. Material choice is another major factor. Corrugated packaging might last only a few trips, while plastics designed with the right impact resistance, UV stability, and weather tolerance can circulate for years. It’s about matching the material to its environment and expected lifespan. Q: Are there specific materials where circularity is advancing fastest — and others where it’s still a struggle? A: Rigid plastics — things like pallets, totes, and containers — are advancing the fastest because they’re high volume and easier to process. PET, HDPE, and polypropylene are particularly strong candidates because they can be reprocessed multiple times. Where we still struggle is with single-use, multi-layer packaging — the snack wrappers, films, and laminates that mix materials for barrier protection or freshness. Those layers make recycling extremely difficult. There’s exciting research happening in that space, but large-scale solutions are still developing. Q: What does a more circular plastics industry mean for jobs and skills in Southeast Michigan? A: It means opportunity — but it also means we need education. There isn’t a single university or technical program I know of that teaches recycling as part of its core curriculum. You can find polymer science programs but not recycling operations or circular systems. Training people for this industry is critical. If you lose a skilled recycling technician, you can’t just hire a replacement from a temp agency. It takes months or even years to become proficient. And with plastics recycling, mistakes are costly — something as simple as

How Sesame Solar is Aiming to Build a Mobile Clean Energy Future

Sesame Solar, based in Jackson, Michigan, is pioneering a new model for clean, mobile power. The company’s self-generating “nanogrids” — compact, solar- and hydrogen-powered units that deploy in minutes — are designed to deliver renewable electricity anywhere it’s needed. From emergency response and telecom operations to defense and community resilience, the technology provides an alternative to the diesel generators that have long powered temporary and remote sites. SBN Detroit interviewed co-founder Lauren Flanagan about redefining energy resilience, the challenges of scaling clean power, and why Michigan is the right place to lead this transformation. Q: Tell me about Sesame Solar — what inspired it, and how did it begin? A: After Hurricane Katrina, it hit me that extreme weather was becoming more frequent and more severe. And it was clear that government alone couldn’t handle the response. Every time disaster struck, I saw diesel generators being deployed to restore power, even though they caused massive environmental damage and logistical problems. That was the “aha” moment. I wanted to create a clean, mobile, self-generating power solution that could replace diesel. Q: How did that vision turn into the nanogrid model you use today? A: We realized that to change behavior, we had to make the better solution easier — something that could be deployed quickly, run cleanly, and adapt to different uses. We created a model that is modular and scalable, like Lego blocks. The nanogrids can power emergency offices, communications systems, field kitchens, drone refueling stations and more. The first units were deployed in the Caribbean after Hurricane Maria (2017), and they’re still operating today. From there, we’ve expanded across the U.S. — our systems are used by cities from Ann Arbor to Santa Barbara, and by telecom companies like Comcast, Cox, and Charter. Q: What kinds of situations demonstrate the greatest need for deployable clean power? A: Disaster recovery is one, of course, but our nanogrids are also being used anywhere grid power is unreliable or unavailable. The Air Force and the Army Corps of Engineers use them for unmanned operations, including surveillance and communications. We’ve also developed hydrogen-powered drone refueling stations with partners like Heven Aerotech. We’re seeing use cases across emergency management, defense, telecommunications, and community resilience — really, any situation where people need dependable, sustainable power quickly. Q: What challenges come with making energy both mobile and self-generating? A: It’s hard. To make something that sets up in 15 minutes and runs off solar and hydrogen, you need deep integration between hardware, software, and automation. We hold multiple patents, and our engineering team has solved challenges around rapid deployment, autonomous energy management, and safety. Every component — from insulation and vapor barriers to passive energy systems — contributes to efficiency. We have a unit deployed with the Army Corps of Engineers that’s been running unmanned for nearly a year with zero downtime. Imagine if a diesel-powered generator was running for that long. And maintenance of the unit consists of blowing sand off the panels twice a year because it’s located in the desert. That’s the level of reliability we’re aiming for. Q: How do you measure the environmental benefits compared to diesel generators? A: We quantify it in CO₂ savings. Our software platform tracks every kilowatt generated and consumed, calculating gallons of diesel avoided and total emissions saved in real time. It’s data our customers can use to validate their sustainability goals. Beyond emissions, diesel generators are noisy, polluting, and often dependent on supply chains that fail during crises. A self-sustaining nanogrid avoids all of that. Q: You moved the company from California to Michigan. Why build here? A: Honestly, I wouldn’t have opened this business in California. Michigan offers lower operating costs, a strong manufacturing base, and deep expertise in mobility and electrification — all areas that align with our long-term vision to make nanogrids more automated. The state has a world-class supply chain. We buy from companies like Alro Steel, we hire engineers locally, and we also source as locally as possible. I like to say we take a farm-to-table approach to manufacturing: how much can we build right here in Michigan? Q: What opportunities does this create for Michigan’s workforce and suppliers? A: We’re growing quickly — we have 23 employees and are hiring more technicians now. The roles require multidisciplinary skills like fabrication, welding, mechanical, and electrical. Increasingly, there are opportunities for advanced computer-assisted and AI-driven roles too. Michigan’s existing fabrication and automotive supply chain is a huge advantage. As that sector transitions toward electrification, it’s opening new opportunities for clean-tech manufacturing to scale. Q: What does the next decade look like as extreme weather becomes more frequent and the energy transition accelerates? A: It’s predicted that we’ll see a significant number of billion-dollar weather events in the next five or six years. Even as we make progress in slowing climate change, we’ll still need to adapt. That’s where mobile, renewably powered systems can come in. They bridge the gap between infrastructure and immediacy — bringing clean energy wherever it’s needed. I’m an optimist. I believe the technology exists to stabilize the climate, but it won’t get easier before it gets better. At Sesame Solar, our mission has always been about people, planet, and profit. It sounds a bit fluffy, but we are working to help communities, companies, and governments prepare for the future — not just by responding to disasters, but by rethinking how we power the world in the first place. Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on sustainable business practices in and around Detroit.

Circular by Design

Revolin Sports, a Holland, Michigan-based startup founded by siblings Hugh and Greta Davis, is aiming to change how sports equipment is made — starting with the fastest-growing sport in America: pickleball. The company is using renewable materials, energy-efficient manufacturing, and recyclable design to lower the environmental footprint of high-performance paddles. SBN Detroit interviewed Hugh Davis, cofounder of Revolin Sports, about how sustainable materials, circular manufacturing, and local partnerships are reshaping the future of sporting goods manufacturing in Michigan and beyond. Q: What first motivated you to build a sustainable paddle brand? A: I started playing pickleball in high school and eventually started competing semi-professionally. As a sponsored player, I kept noticing a pattern — paddles were breaking constantly. My friends’ paddles were breaking, too, so I began repairing them in my garage. That side hustle evolved into a deeper curiosity about how to make paddles better. I studied engineering at the University of Michigan, which gave me insight into materials and design, and I realized there was an opportunity to build something higher performing and better for the planet. Ultimately, my vision was to revolutionize equipment by using natural fiber and renewable linens – that’s where the name Revolin comes from. Between 2015 and 2020, my sister and I built and tested a few hundred prototypes, experimenting with new combinations of renewable materials like flax and hemp. Eventually, we landed on a formula that delivered superior performance with less vibration and weight — and dramatically reduced emissions. That became the foundation for Revolin, which we launched in 2020 with the world’s first 98% reduced-emission flax paddle. Q: Most high-performance paddles today use carbon fiber, which has a large carbon footprint. How do you assess and reduce that impact? A: Most paddles are made from carbon fiber or fiberglass, and those materials definitely have value. They’re lightweight, stiff, and durable. But they’re also petroleum-based, energy-intensive to produce, and nearly impossible to recycle. We evaluate each material’s embodied emissions — how much carbon it takes to produce — and calculate the footprint per paddle based on the exact quantities used. Our data shows a 50-75% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions per unit compared to traditional paddles. We also manufacture in the U.S. using primarily U.S.-sourced materials. That reduces transportation emissions and gives us control over our process, from sourcing to final product. Most of our emission reduction comes from our material choices — how we layer and combine them to improve both environmental impact and performance. Q: You use BioFLX™ (hemp/flax composites) and LavaFLX™ technologies. What are those materials, and how did you develop them? A: BioFLX™ refers to our biocomposite made from hemp and flax — two plants that grow tall and fast and contain some of the strongest natural fibers on Earth. We extract, weave, and layer those fibers in specific orientations, then press them together using a low-energy resin system. The result is a lightweight, rigid panel that reduces vibration and is fully recyclable. LavaFLX™ works similarly but uses fibers derived from volcanic rock. The rock is melted, purified, and extruded into filaments thinner than human hair. It’s less energy-intensive to process than carbon fiber and easier to recycle, while offering exceptional power and spin. We also combine the two to create BioFLX™ Plus — a hybrid that balances strength, elasticity, and environmental benefits. We’ve patented how we layer and weave these materials, and we’re already exploring how to use them in other industries like skis, snowboards, and paddleboards. Q: Where do you see the biggest energy or waste inefficiencies in paddle production? A: Two main areas: waste and durability. In traditional sporting goods manufacturing, roughly one-third of materials end up as scrap. A lot of that comes from cutting patterns or using oversized molds. Most of the industry’s production is overseas, so there’s also significant energy and shipping waste. We focus on small-batch production to minimize scrap and leverage leftover material wherever possible. Then there’s product lifespan. Some players go through a dozen paddles a year because they’re not built to last. We design ours for durability — and we are piloting a program to refurbish and recycle paddles at end-of-life. Q: What steps have you taken to make your packaging more sustainable? A: We keep packaging simple and circular. All of it is made from recycled cardboard that’s fully recyclable again. We print with algae-based inks, which have a lower footprint and fewer toxins than petroleum-based inks. And we use minimal packaging — no excess plastic or unnecessary filler. Q: How does your paddle recycling program work? A: We recently launched a pilot program with our Rise paddle, which was designed to be nearly 100% recyclable. Once the grip wrap is removed, we can grind the rest of the paddle and turn it into pellets for injection molding or even filament for 3D printing. Customers who return their paddles get a discount on a new one, and we reuse the material to create other products. The program is still in its beta phase, but we’re collecting paddles and testing processes now. Within the next year or two, we plan to scale it into a full circular system. Q: What are the biggest challenges you face? A: Cost is definitely one. Our materials are unique and sourced from small, innovative suppliers. Building everything in the U.S. adds cost too, but it allows us to control quality, innovate quickly, and maintain transparency. Availability can also be challenging. These materials are newer, niche, and sometimes hard to find in the right weights or thicknesses. Q: How do consumers respond to the higher price point? A: It depends. Some buyers come to us because of sustainability, others because of performance. Once players feel the paddle — the lack of vibration, the control, the extra spin — they recognize the performance value. It’s not just a sustainable paddle; it’s a better paddle. We’ve worked hard to keep pricing competitive without passing our higher costs directly to consumers. And once people learn

Michigan-Founded Tech Company, Motmot

Aging drinking water systems are one of Southeast Michigan’s most pressing infrastructure challenges. Many pipes in the region date back to World War II, built with materials now at the end of their service life. Combined with harsh freeze-thaw cycles and decades of underinvestment, the result is frequent leaks, water main breaks, and costly emergency repairs. Motmot, a startup located in Detroit, is tackling this challenge by deploying robotic technology directly inside live water mains. By providing utilities with condition data they’ve never had before, Motmot aims to shift water infrastructure management from reactive crisis response to proactive planning. SBN Detroit interviewed Elliot Smith, the company’s CEO and Co-Founder, about Southeast Michigan’s unique vulnerabilities, the role of technology in creating more equitable water systems, and how utilities can prepare for the future of smart infrastructure. Q: From your perspective, what makes Southeast Michigan’s drinking water systems especially vulnerable? A: Southeast Michigan has some of the oldest drinking water systems in the country. Much of the pipe was placed around World War II, often using cast iron that is now at the end of its life. Add in our freeze-thaw cycles, which cause pipes to expand and contract, and the risk increases. We also have a history of underinvestment — the goal has long been to replace about 1% of the system per year, but that hasn’t happened consistently. In the Detroit metropolitan area alone, there are 13,000 to 14,000 miles of water main pipe. When one failure occurs, it can cascade into emergency work for other cities connected to the same transmission systems. Q: How does your technology change the timeline for cities and utilities — shifting from reactive maintenance to proactive decision-making? A: Traditionally, utilities only learn about problems once a water main fails. That means flooding, emergency repairs, added operational expenses, and public safety risks. What we’re fighting against is that cycle. Our technology provides data before mains fail. It’s about making the unknowns known and helping cities get ahead of the problem. Q: How do you see technology helping ensure that water system improvements are not only efficient but also equitable? A: Equity starts with visibility. Communities with fewer resources often can’t afford inspections, which means they experience more frequent issues. If we can lower the barrier to entry and make inspections affordable, every community has the chance to see what’s happening in their system. That helps mitigate risk and plan for future projects. At the same time, state revolving funds and stronger datasets can help overburdened communities secure the resources they need. Q: Where is Motmot in development today? A: We’re in the pilot stage now. We’ve kicked off our first pilot with the city of Detroit – I was especially happy that Detroit was the first city to take a chance on us. We are working through the American Water Works Association network. We already have more than 50 communities on our waiting list. That said, we’re being very intentional about not moving too fast. We want safe, effective pilots for every community we work with. My goal is to have 10 pilots started by the end of the year. Q: Beyond financial costs, what are the biggest environmental consequences of undetected water loss? A: Water loss is significant. A leak means residents are paying for water they never actually use. But it’s not just lost water — it’s wasted energy and chemicals as well. That water was treated, pumped, and disinfected before it ever leaked into the ground. In Michigan, reducing water loss directly supports our sustainability goals by conserving Great Lakes water and reducing the energy tied to treatment and pumping. Q: What do you see as the biggest hurdles to widespread adoption of smart water infrastructure? A: Risk perception is one. This is a relatively new technology, and water systems are old and often archaic. The mentality of “if it’s not broke, don’t fix it” is strong — but the truth is, much of the system is broken. We also have to prove our technology won’t contaminate systems or interfere with daily operations. And public works departments are already stretched thin. They’re chasing main breaks and doing emergency repairs, so adding another piece of technology can feel like a burden at first glance. Q: Motmot is entering a highly regulated, risk-averse sector with a disruptive idea. What lessons can other businesses learn from your approach? A: It really comes down to partnerships and credibility. We started incubating at the university level, then built credibility through the American Water Works Association. You have to build trust in the ecosystem — with regulators, utilities, and stakeholders. If you have a big idea, you can’t just drop it into the market. Plant seeds, engage stakeholders, and earn advocates who will vouch for you. Q: What do you see as the next frontier in smart water infrastructure — and how might Michigan businesses and communities prepare? A: Integration. In industries like oil and gas, systems like inspections, billing, and modeling are linked because there’s money to be made in efficiency. In the municipal space, those systems are often siloed. Breaking those silos down — connecting engineering departments, utilities, and technology platforms — is the next frontier. Michigan is well positioned to lead in this. We have a concentration of utilities, strong players like the Great Lakes Water Authority, and research universities investing heavily in this space. If we can integrate and apply technology in practical ways, not just in pilot projects, we can move from innovation theater to real-world results. Q: When you talk with water leaders across the U.S., what pain points come up most often? A: There are three that come up repeatedly. First, aging infrastructure — in some places, water mains date back to the 1840s. Second, visibility. Public works is an underappreciated industry. People see parades and fireworks, but not the crews that make daily life possible. That lack of visibility has led to chronic underinvestment. Third, affordability. This space has

AquaAction Chooses Detroit for U.S. Headquarters

Founded in Canada, AquaAction is a nonprofit dedicated to tackling freshwater challenges through innovation and entrepreneurship. Now, the organization has chosen Detroit as its U.S. headquarters — a choice made because of Southeast Michigan’s role as a steward of the Great Lakes and a launchpad for water-tech solutions with global reach. Through initiatives like the AquaHacking and AquaEntrepreneur programs, AquaAction supports young innovators as they transform ideas into real-world technologies. SBN Detroit interviewed President Soula Chronopoulos about why Detroit was selected, the challenges and opportunities facing the region, and how water-tech could shape the next phase of Southeast Michigan’s economy. Q: What makes Detroit—and Southeast Michigan overall—a compelling region for water-tech innovation and freshwater stewardship? A: There’s a powerful momentum building in Detroit. The city has long been a symbol of resilience and grit, and now it’s fueling a new wave of entrepreneurial energy unlike what we’ve seen in other regions. With freshwater and climate change in the global spotlight, Detroit and Southeast Michigan are uniquely positioned. Sixty percent of the global economy depends on freshwater, and this part of Michigan sits on some of the world’s most critical reserves. The Great Lakes hold 21% of the planet’s freshwater resources, making them both a tremendous asset and a frontline target in the fight against climate change. This region has the chance to build something extraordinary — an economy rooted in water technology that can emerge directly from the Great Lakes. Q: How does AquaAction’s presence here help address regional freshwater challenges versus other parts of North America? A: When we considered where to establish our U.S. base, Detroit quickly stood out. Why? Because this area faces some of the toughest water challenges in the country: Flooding, affordability, pollution, and the legacy of crises like Flint. At the same time, there’s an eagerness here to be part of the solution. Detroit is a real-world test bed. If solutions can work here, they can scale across the U.S. and beyond. That’s why I often say the Midwest — and Detroit in particular — has the potential to become the Silicon Valley of water tech. Q: Can you discuss examples from the AquaHacking and AquaEntrepreneur programs that have particular relevance to Southeast Michigan? A: We ran our first Great Lakes binational challenge in 2023, and the response was incredible. Over 250 people joined, 45 teams were formed, and we launched 10 companies out of Michigan and the Great Lakes region. A few examples stand out: Motmot, based at Newlab, uses underwater robotics to detect leaks in aging water infrastructure. They’ve completed more than 40 projects. Myconaut uses bioengineered mushrooms aiming to remediate contaminated soil and keep lead out of drinking water. They recently won a grant and are testing their technology right here in Michigan. Other ventures include predictive flood modeling tools for cities and digital water management systems — both highly relevant to Southeast Michigan’s infrastructure challenges. In Quebec, similar efforts helped build a $200 million water-tech economy. Imagine what’s possible here. Q: How are young entrepreneurs being supported to translate their water-tech solutions into real-world applications in this region? A: We take a different approach. First, we’re a charity, but we’re also entrepreneurs ourselves. That perspective shapes how we build support for innovators. We’ve created an ecosystem where entrepreneurs can partner with subject-matter experts to validate their solutions. We then connect them with business leaders who help refine their models, open doors, and provide mentorship. Finally, we ensure they get into the field to test and apply their work. In Michigan, we anticipate engaging over 1,000 students and innovators in the coming years. We’re also focusing on communities including those with high unemployment. Q: What are the most pressing water-related challenges Southeast Michigan must address now—and in the coming years? A: Infrastructure is the biggest challenge. Much of it is aging and in need of major investment. Beyond that, flooding, pollution, and overall water management remain pressing concerns. There’s also the question of innovation. Detroit’s history in the automotive industry raises an important question: what comes next? I believe water technology can be the next major economic driver. The region already has supply chains, industrial capacity, and expertise that can be leveraged to build a world-class water-tech sector. Q: What barriers are startups or innovators encountering when bringing solutions to market locally? A: The greatest barrier is awareness. Climate conversations often focus on carbon, while water is overlooked. Yet 60% of the global economy runs on water. It is the lifeblood of everything, but we rarely treat it that way. That said, we’re beginning to see a shift. Policymakers, business leaders, and communities are starting to recognize the true value of water — not just as an environmental concern, but as an economic and security issue. Q: With U.S. headquarters now in Detroit, what kinds of economic or social impacts do you anticipate? A: There are two main areas of impact: Jobs and community. In Canada, we’ve helped create around 400 jobs, and we expect to do the same here. Every time we run an AquaHacking or AquaEntrepreneur program, we typically launch 10–20 companies. That means new businesses, new pilot projects, and new career opportunities. We’ve committed to the MEDC that within 12–18 months, we expect up to 35 new businesses to be launched, several pilot programs to get off the ground and at least 10–12 new staff hired at our Detroit office. Equally important is the community impact. Water is a human right, and it brings people together. We’re cultivating a new generation of innovators who see water not just as a resource but as a foundation for equity, resilience, and growth. Q: How do you envision long-term freshwater security, innovation, and resilience evolving in Southeast Michigan? A: Michigan is at a turning point. Just as it once led in mobility, the state can lead in water — in quality, flood management, pollution control, and technology development. The region has the knowledge, the infrastructure, and the industrial base to