Detroit Entrepreneur Builds Eco-Conscious Candle Brand

Unique Monique Scented Candles, a Detroit-based business founded by Monique Bounds., aims to produce candles and household products with clean ingredients and local supply chains. What began as a personal hobby during college has evolved into a full-time venture producing coconut oil and soy-based candles made with essential oils and locally sourced materials. SBN Detroit interviewed Bounds about launching a sustainable product line, sourcing challenges in Michigan, and how small manufacturers are navigating the growing demand for eco-conscious home goods. Q: Tell us how Unique Monique began and what motivated you to turn candle-making into a business. A: I started making candles about five or six years ago. It began as a hobby – something calming and creative that helped me manage stress while balancing college classes I was taking and work. I shared them with friends and family, and the response was positive. As I continued experimenting, I began taking business mentoring classes. My mentor helped me understand how to turn my hobby into a business, including forming my LLC and developing relationships with local stores. That’s when I realized there was real potential to grow this into something sustainable. Over time, I also became more intentional about ingredients. I noticed some of the natural components I was using felt better for people in my own household, especially those with allergies or respiratory sensitivities. That shaped the direction of the brand. Q: What distinguishes your candles from traditional scented candles on the market? A: The foundation of my candles is soy flakes derived from soybeans and coconut oil, blended with pure essential oils. I avoid harsh chemicals and synthetic additives. The goal is to create a cleaner burn with minimal soot and no heavy chemical residue. For me, sustainability starts with setting non-negotiable ingredient standards. I use boiled wax methods, essential oils, and thicker glass jars to prevent cracking and extend product life. Packaging also matters. I try to use materials that are safe and environmentally responsible. Q: From your perspective, what does building a genuinely eco-conscious product require beyond just ingredients? A: It requires discipline. Sustainability isn’t something you add later, it has to be built into your foundation. That means being selective about suppliers, understanding where materials come from, and balancing cost with integrity. Many ingredients are processed in ways that aren’t obvious at first glance, so sourcing responsibly takes research. I’ve also had certain ingredients lab tested to ensure they align with my standards. Beyond ingredients, packaging, waste reduction and long-term product use all matter. I think about how the product lives in someone’s home and what happens after it’s finished. Q: How are consumer attitudes around indoor air quality and “clean” products evolving? A: Consumers are more informed now. People ask questions about what’s in their products. They want to know about essential oils, wax types, and where ingredients come from. There’s more awareness around chemical exposure in everyday products. At the same time, there are misconceptions. For example, some people have concerns about soy wax because of misinformation online. Education is important – not everything labeled “natural” is automatically good or bad. It’s about understanding the sourcing and processing behind it. Q: You also emphasize sourcing locally. Why is that important to you? A: Whenever possible, I source ingredients locally in Michigan. I want to keep money circulating within the state and reduce transportation impact. Local sourcing helps minimize carbon footprint and supports other small businesses. It does require careful vetting. But I believe strengthening local supply chains is part of long-term sustainability. Q: How has community engagement played a role in your growth? A: Community events have been very important. I’ve participated in local showcases like the Henry Ford Museum during Black History Month, as well as events connected to the NFL Draft and the Detroit Grand Prix. These events create opportunities not only to sell products but to educate consumers about clean ingredients and sustainable manufacturing. Being present in the community has helped build awareness. Q: Beyond candles, are you expanding into other product categories? A: Yes. I recently launched an antibacterial laundry detergent made with biodegradable, plant-based ingredients. It’s currently carried by More Herbs, a local health and wellness store. I’m also exploring home cleaning kits, and other self-care products. The long-term vision is to build a marketplace that supports other small businesses with similar sustainability values. Q: Looking ahead, what does growth look like for Unique Monique? A: Right now, most of the business is online, but I do have a physical office location. I’d like to expand retail partnerships and possibly open a brick-and-mortar space in the future. Workshops and classes are another goal… teaching others about candle-making and sustainable product development. Ultimately, I want every decision the company makes to support healthier homes, stronger communities and a cleaner environment. Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on sustainable business practices in and around Detroit.

Eastern Market Expands Investment in Local Growers

Eastern Market Partnership, in collaboration with the City of Detroit’s Office of Sustainability Urban Agriculture Division, has announced $240,000 in grant funding to support Detroit-based farmers and farmer collectives. The grants will advance food access, climate education, sustainable land use, and economic opportunity, with priority given to Black- and Indigenous-led farms, youth-led initiatives, and projects rooted in historically disinvested neighborhoods. The recipients – ranging from cooperatives and community gardens to individual urban farms – were selected through a competitive request for proposals process. The funding builds on Eastern Market’s broader efforts to strengthen Detroit’s local food ecosystem, including expanded purchasing programs for urban growers, wholesale distribution improvements, and ongoing infrastructure investments such as the redevelopment of Shed 7. SBN Detroit interviewed Katy Trudeau, president and CEO of Eastern Market, about why this investment matters now, how it supports Detroit’s evolving urban agriculture landscape, and what it signals for the future of local food systems. Q: From Eastern Market’s perspective, why was this the right moment to invest in Detroit’s urban farmers at this scale? A: We’ve been building toward this moment for a few years. In 2023, Eastern Market was awarded Local Food Purchasing Assistance funding through the USDA, which created a dedicated channel for purchasing produce from Detroit’s urban farms. That program reinforced something many of us saw during the pandemic – long supply chains are vulnerable, and there is real importance in strengthening local food systems. Through that federal program, roughly 60 percent of our purchasing went directly to Detroit-based urban growers, with the remainder sourced from regional partners. It proved that we had both the supply and the community demand to sustain a more localized system. The City Council’s decision to award this new grant funding gives us another tool to invest directly in that growing network of urban farmers who are feeding Detroiters. We’ve long supported many of these growers through Saturday Market vending opportunities and other initiatives. This grant allows us to deepen that commitment and build on the foundation already in place. Q: Urban farming has long been part of Detroit’s identity. How do you see its role evolving today? A: Urban agriculture is a micro-industry in Detroit, but it plays an outsized role. It is directly responsive to the need for shorter supply chains. Growing food locally that we can eat locally strengthens access to nutrient-dense food and reduces reliance on distant systems. Many of the farms receiving grants are not only producing food but also teaching residents how to grow their own. That educational component is critical. It builds long-term capacity and strengthens food security at the neighborhood level. There are also broader impacts. Urban farms create gathering spaces where neighbors meet neighbors. They generate small-business opportunities and, in some cases, provide employment and workforce development. They help stabilize vacant land and turn it into productive community assets. It’s economic development, environmental stewardship, and social infrastructure all in one. Q: Why was the focus on Black- and Indigenous-led farms essential to the design of the program? A: Detroit is a majority-Black city, and much of the farming happening here is led by Black growers. We want investment dollars to reflect and support the communities where the work is taking place. One of the grant recipients is an Indigenous farmer who is focused on sharing the cultural importance of Indigenous agricultural practices. That educational lens adds another layer of value to the program. Supporting Black- and Brown-owned businesses has long been part of Eastern Market’s mission. Our Saturday Market vendors represent a wide diversity of entrepreneurs. This grant aligns with that broader commitment to equitable investment and representation. Q: What does food sovereignty mean in a Detroit context? A: To me, food sovereignty is about creating the ability for people to feed themselves locally, without complete reliance on large corporations or distant supply chains. Eastern Market has always played a role in that. As a public market, we provide a space where Detroiters can shop locally and support regional growers. The pandemic made clear how important local capacity can be. This grant program also supports farms that are teaching others how to grow, preserve, and prepare food. It’s about increasing independence and resilience at the household and neighborhood level. Q: How does supporting small-scale, community-based growers impact the broader regional food system? A: Michigan has a robust and diverse agricultural industry, thanks in part to our climate and access to freshwater. What we’re seeing with urban agriculture is the next generation of that legacy. Urban farming represents a micro-scale version of a long-standing agricultural tradition in Southeast Michigan. As we continue investing in it, we’re strengthening a more diversified regional food economy. Over time, as urban agriculture grows as an industry, it can become a stronger economic driver. It also reinforces the importance of regional and state-level support for local food systems. Q: How does urban agriculture reshape the conversation around Detroit’s vacant land? A: My background is in urban planning, so I think about land use a lot. Vacant land can serve different purposes depending on the context. Some farms are temporary land uses that beautify or remediate vacant lots. Others have become permanent economic enterprises that are deeply integrated into their neighborhoods. They are respected, loved, and woven into the urban fabric. Urban agriculture can address vacant land challenges in multiple ways, whether through short-term stabilization or long-term economic development. It gives neighborhoods options. Q: Looking at the selected recipients, what excites you most about the diversity of approaches represented? A: The diversity is incredibly exciting. When we reviewed the applications, we were struck by how much innovation is happening across the city. Some grantees are focused on cooking classes and community nutrition education. Others, like the Grow Moore Produce Cooperative, are leveraging the collective strength of multiple farms to provide training and shared resources. There are also initiatives that help growers turn what they cultivate into value-added products for sale at farmers’ markets. From seed starting to preservation

Building More Sustainable Homes Through Automation

Citizen Robotics is a Detroit-based nonprofit that advances the use of robotics and digital manufacturing in residential construction, focusing on improving productivity, sustainability, and long-term affordability. Best known for its early work in 3D-printed housing, it explores how alternative construction methods and new financial models can reduce material waste, lower lifetime operating costs, and enhance the resilience of homes. SBN Detroit interviewed Tom Woodman, founder and president of Citizen Robotics, about why housing has lagged behind other industries in adopting new technologies, the structural barriers facing innovative construction methods, and what it would take for models like 3D-printed housing to move from experimentation to scale. Q: Tell me about Citizen Robotics and the impetus behind it. A: The homebuilding industry largely missed the digital revolution. Productivity has been flat for decades and, that has directly contributed to the rising cost of new construction. It has also limited progress on sustainability, from material efficiency to energy performance. At the same time, the industry has struggled to attract younger workers, in part because it’s perceived as manual and outdated. Citizen Robotics was formed in response to that dynamic. The idea was to demonstrate that a robotic future for homebuilding is not only possible, but achievable now. We centered our early work on 3D construction printing because it brings together robotics, digital design, and material innovation in a way that could fundamentally change how homes are built. Q: Citizen Robotics drew early attention for its work in 3D-printed housing. Where is the organization today? A: That early work generated a lot of interest from the community and the media. One of the most important outcomes was that people could physically experience the technology. Thousands of people toured the house, touched it, walked through it, and asked questions. You could see perceptions shift once people understood what was actually possible. Today, we’re working more directly with municipalities and partners to move toward a structure that can support real-world deployment. We’re exploring a for-profit framework that would allow 3D printing to achieve broader impact, including a model we call “Build for Equity,” which combines rental housing with shared equity over time. Q: In your experience, what are the biggest barriers to scaling new housing technologies like 3D printing? A: Many people assume the barrier is more innovation — better robots, better materials. In reality, we’ve shown that even existing robotic systems can deliver meaningful gains, not only in productivity but in material efficiency and long-term performance. The real barriers fall into four areas: market acceptance, continuity of capital, industry conservatism, and a funding gap around productivity. Housing is expensive no matter how it’s built, and resale value is always top of mind. Anything outside the mainstream creates anxiety for buyers, lenders, and developers. Sustainability benefits, such as durability, resilience, and lower operating costs, are rarely reflected in how homes are valued or financed, which makes adoption harder. There’s also a Catch-22. To make homes cheaper, you need volume and repetition. But to get volume, you need lenders to underwrite projects, and they need comparable data that doesn’t yet exist. Q: Why has housing been so slow to adopt automation compared to other industries? A: A big part of it comes down to incentives. Construction largely delivers what the system pays for. The way homes are financed, maintained, and insured often works against affordability over the long term. If we want healthier, more durable homes, we need to reward innovation rather than cost-cutting that degrades quality. Right now, the system works well for those already positioned to profit from it. Changing outcomes requires changing incentives. Q: From your vantage point, where is the greatest opportunity to rethink how homes are built? A: One of the biggest opportunities is Detroit’s inventory of residential lots, combined with a different financial model paired with industrialized construction methods. Build for Equity is about constructing homes for rent while allowing renters to build equity over time through a shared fund structure. That model allows us to focus on the total cost of ownership. From a sustainability standpoint, materials like concrete offer fire, flood, and storm resilience, along with lower long-term maintenance and operating costs. When homes are evaluated based on total cost of ownership — including energy use and durability — innovation becomes much easier to justify. Q: What does it take to keep an innovation-focused organization viable during periods of uncertainty? A: It’s difficult, particularly in a challenging fundraising environment. But the need hasn’t gone away. Around the world, 3D construction printing is advancing – in Texas, Florida, Ontario, Kenya, Japan, and beyond. We learn from those efforts and adapt what makes sense locally. The key is securing capital for repeatable projects so the technology can move beyond prototypes and generate the data lenders need. Q: What would meaningful progress look like for Citizen Robotics over the next few years? A: Moving from prototypes to a repeatable playbook that lenders are comfortable underwriting. Training and placing at least 60 workers into high-tech construction roles. Scaling projects across multiple municipalities. Michigan has the ingredients to become a proving ground for innovative and more sustainable construction, from advanced manufacturing expertise to policy interest in sustainability. The challenge is unlocking the first wave of projects. Q: What needs to change for innovative housing models to become permanent? A: We need financing structures that optimize for total cost of ownership, not just upfront cost. Philanthropy can play a role in de-risking early projects and funding workforce development. Policy matters too. Zoning reform, incentives for net-zero housing, and support for local job creation all help create space for innovation. With the right mix of public, private, and philanthropic investment, we can keep jobs local, improve housing quality, and move toward a more sustainable construction system. Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on sustainable business practices in and around Detroit.

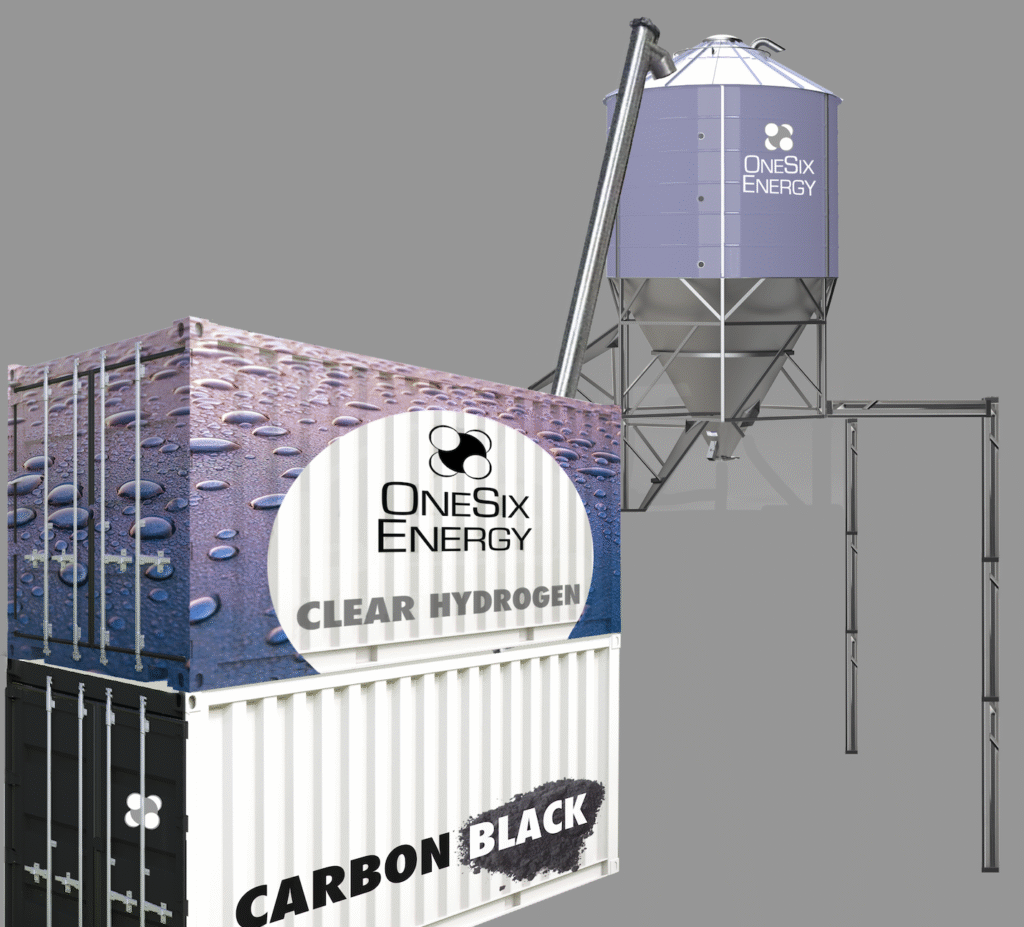

Rethinking Hydrogen Production

Detroit-based OneSix Energy is a clean-energy technology company focused on advancing a lower-carbon approach to hydrogen production. Headquartered at Newlab in Detroit, the startup is developing a proprietary methane pyrolysis system designed to produce hydrogen without carbon dioxide emissions, while also generating solid carbon as a co-product. SBN Detroit interviewed with cofounder Stefan Sysko about the company’s origins, its approach to hydrogen production, and why Detroit is positioned to play a leading role in the next phase of the energy transition. Q: Can you give us the elevator version of OneSix Energy — how it got started, the impetus behind it, and the approach you’re taking to hydrogen production? A: OneSix Energy really began with my co-founder, Dan Darga, who back in 2002 was working at General Motors. He read about the hydrogen economy and immediately knew he wanted to be part of it. He transferred to GM’s fuel cell division in upstate New York, then later worked for a solid oxide fuel cell company. While there, he kept running into the same problem: carbon buildup clogging systems. His perspective was that we were fighting nature instead of working with it. That led him to start thinking differently about surfaces, materials, and how carbon behaves. Dan eventually left to work at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he learned how to take ideas from concept to deployment in extreme, real-world conditions. He combined these two experiences, refined them, and approached me. I’ve been a lifelong entrepreneur, and I felt I had one more startup in me — one that could genuinely address a major global challenge. We incorporated OneSix Energy nearly two years ago, bootstrapped the initial design and modeling, filed a patent that’s now pending, raised a friends-and-family round, built and independently tested a prototype, and are now moving toward a pilot phase. Q: What problem is hydrogen uniquely positioned to solve that other energy carriers can’t? A: Hydrogen is incredibly energy-dense by mass, and when it’s used, the only byproduct is water vapor. It’s versatile — it can be used as a fuel for power generation or as a chemical feedstock. Hydrogen has been called “the fuel of the future” for decades but it’s difficult and expensive to produce cleanly. Today, about 90 percent of hydrogen is made using steam methane reformation, which is cheap but very dirty — roughly 11 tons of CO₂ for every ton of hydrogen produced. Electrolysis, on the other hand, is clean but extremely expensive and water-intensive. It requires fresh water, significant electricity, and even when powered by renewables, you lose about half the energy in the process. When you look at sectors like data centers — which already consume enormous amounts of electricity and water — electrolysis actually worsens the problem. Our system is different. We’re off-grid. We recirculate a fraction of the hydrogen we produce to power our reactor, so we don’t need external energy, and we don’t use water. In fact, we generate fresh water as a byproduct. Q: Can you explain methane pyrolysis and what OneSix Energy has developed? A: Methane pyrolysis involves taking methane — CH₄, the main component of natural gas — and breaking it into hydrogen and carbon using high temperatures in the absence of oxygen. Because there’s no oxygen, you don’t form CO₂. Instead, you produce solid carbon. That solid carbon – or “carbon black” – is actually valuable. It’s used in products like tires, shoe soles, and industrial materials. There’s a roughly $40 billion global market for carbon black today. Our goal is to upcycle that carbon while producing hydrogen at a lower cost than electrolysis, without water use or external energy input. Q: Hydrogen production often involves trade-offs. What innovations are helping overcome those barriers? A: Right now, the industry is stuck between options that are either cheap and dirty or clean and expensive. What’s changing is the recognition that we need new pathways — not just incremental improvements. Innovations in materials science, reactor design, and system efficiency are making approaches like methane pyrolysis viable at scale. The key is eliminating emissions without introducing new resource constraints. Q: Where do you see the earliest and most impactful applications for clean hydrogen? A: Two areas stand out immediately: data centers and shipping ports. Ports face increasing regulatory pressure because of emissions from ships idling while docked. Hydrogen-powered equipment and shore power could significantly reduce pollution while keeping operations moving. We also see opportunities in power generation for buildings, factories, and industrial facilities. Long-term, hydrogen fuel for heavy-duty transportation — Class 8 trucks, for example — is very compelling. Electrifying those vehicles requires massive and expensive batteries that reduce payload capacity. Hydrogen avoids that issue. Q: Why build a clean-energy technology company in Detroit? A: Detroit put the world on wheels. There’s no reason it shouldn’t lead the energy transformation. We’re at Newlab, surrounded by engineers, manufacturers, and people who understand how to scale physical systems. Detroit is a perfect microcosm — a place where you could demonstrate how an entire city transitions to clean energy. Plus, I was born and raised in the city, so it’s home to me. Q: What misconceptions do you encounter most often about hydrogen? A: The first is safety. People immediately think of the Hindenburg. But hydrogen is actually lighter than air and dissipates quickly, whereas gasoline fumes stay low and linger. When you look at safety data, hydrogen performs very well compared to other fuels. The Hindenburg taught us the hard way that we need to develop unique handling procedures for hydrogen – and we have. Q: What should Michiganders understand about hydrogen’s role in a sustainable energy future? A: Michigan potentially has significant natural hydrogen resources, which should be explored. But we need to remember that it will likely be years, if not decades, before that becomes viable, We also have the Great Lakes — which must be protected. If all hydrogen today were produced via electrolysis, the water consumed would be equivalent to Lake St. Clair

Inside Michigan’s Environmental Justice Landscape

Regina Strong serves as Michigan’s first Environmental Justice Public Advocate, leading the state’s Office of the Environmental Justice Public Advocate. Her role focuses on addressing environmental justice concerns raised by communities, helping residents navigate environmental systems, and working across state agencies to improve equity in environmental decision-making. SBN Detroit interviewed Strong about the challenges communities are facing across Michigan and what environmental justice work looks like in practice. Q: As Environmental Justice Public Advocate, what does your work look like day to day? A: There really is no typical day. This role was created to address environmental justice concerns and complaints, to advocate for equity, and to help communities navigate systems that can feel opaque or inaccessible. That can mean many things. On a given day, I might be working on our Environmental Justice Screening Tool as we migrate it to a new platform, meeting with one of our 43 grantees across the state, or sitting down with other state departments or divisions within EGLE, where my office is housed. Other days are spent directly with community members – listening to concerns, helping them understand what levers exist, and figuring out how to move forward. The work ebbs and flows depending on what’s happening in communities. Over the past seven years, we’ve seen some issues emerge seasonally, in response to new development, extreme weather, or long-standing infrastructure issues. Ultimately, my work is deeply relational and constantly evolving. Q: What are the most pressing environmental justice issues you’re hearing across Michigan and how do they differ between urban, suburban, and rural communities? A: There’s actually a lot of overlap across geographies. Whether people live in dense urban neighborhoods, suburban communities, or rural areas, we consistently hear concerns about water – lead service lines, contaminated wells in rural areas, and flooding. Air quality is another major issue, especially near industrial corridors or transportation infrastructure. In more densely populated areas, concerns often cluster around industry, waste facilities, landfills, and cumulative air pollution. In rural areas, it may be wells, septic systems, or access to clean drinking water. Across all regions, energy burden comes up frequently, particularly during winter months, when households are forced to spend a disproportionate share of income on utilities. Climate change is amplifying many of these issues. Flooding, power outages, and extreme weather events are becoming more common, and their impacts are not evenly distributed. The underlying issues may differ by location, but the throughline is vulnerability tied to infrastructure, income, and exposure. Q: What are the hardest gaps to close when translating community concerns into action? A: One of the biggest challenges is that environmental justice issues rarely fall under a single authority. A concern may involve state permitting, local zoning, county health departments, and federal regulations all at once. Our office often helps communities navigate those layers. From an environmental justice perspective, equitable access to decision-making is critical. We work to ensure voices are heard, especially in communities that have historically been underserved. We do a lot of resilience planning in – for example – the 48217 ZIP code (Southwest Detroit) in the heart of a very dense industrial corridor. We also work with communities near hazardous waste facilities and communities with drinking water concerns. Many of these challenges have deep historical roots. Our role is often about helping communities access resources, understand processes, and advocate effectively while acknowledging that solutions are rarely immediate, yet possible. Q: To that end, how does history complicate environmental justice work today? A: History matters a great deal. Many environmental regulations around air and water are set at the federal level and applied category by category. Communities, however, experience impacts cumulatively – air, water, land use, and health intersecting in daily life. That mismatch creates tension. Residents want holistic solutions, but regulatory frameworks don’t always account for cumulative impacts. Before the Clean Air Act and Safe Drinking Water Act, people lived near industrial facilities for decades – and still do. Laws have improved, but legacy exposure and infrastructure decisions remain. Balancing regulatory constraints with community realities is one of the most complex aspects of this work. Q: What structural or systemic barriers are hardest to change? A: Policy is often written within narrow frameworks that don’t always center people’s lived experiences. That’s a persistent barrier. Another is data – how it’s collected, interpreted, and applied. MI EJ Screen, the state’s environmental justice screening tool is designed to help address that gap. It looks at environmental conditions, demographics, and health indicators together, creating a shared reference point for communities, government, and industry. The first version was launched in 2024, and expanding its usability is a priority because shared data helps align conversations and advocacy. Understanding how existing laws interact and where they fall short remains both a challenge and an opportunity. Q: How has your background in clean energy advocacy and community development shaped your approach? A: Where you live often determines the challenges you face. Working in community development and later in clean energy made that clear. Lower-income communities and communities of color are more likely to experience environmental burdens, often due to proximity to industry or aging infrastructure. That perspective informs everything I do. Some issues can be addressed through regulation, but others require working directly with communities to improve daily quality of life. Our Environmental Justice Impact Grant Program is one example – 43 grants statewide, including many in Detroit, supporting grassroots organizations, schools and communities addressing local concerns. This office sits outside of regulatory enforcement, which allows us to take a broader, more human-centered view. Q: How do you think about progress for residents living with impacts right now? A: Progress can look small but be very meaningful. Having a dedicated office focused on environmental justice is progress. Having tools that didn’t exist before is progress. If progress means a senior is no longer dealing with basement flooding because they received support for a sump pump, that matters. We have to focus on both micro-level quality-of-life improvements and

Building the Next Generation of Urban Infrastructure

Founded in 1965, Gensler is a global architecture and design firm working across sectors including urban development, commercial real estate, and civic infrastructure. SBN Detroit sat down with Najahyia Chinchilla, senior associate and sustainability consultant, to discuss mass timber, embodied carbon, and what sustainable construction means for Southeast Michigan. Q: Why is wood re-emerging right now as a serious option for large-scale, urban construction? A: Mass timber blends strength, sustainability, and design quality in ways few materials can. Wood has been used for centuries, but today’s engineered timber products – CLT, glulam, DLT, and NLT – bring a new level of precision, consistency, and performance that aligns with modern building requirements, including strict quality control and predictable fire resistance. Another driver is the industry’s increasing focus on reducing embodied carbon. Compared to steel and concrete structural systems, mass timber can significantly lower a project’s carbon footprint. At the same time, sustainably managed forests contribute to carbon sequestration and biodiversity, while modern processing methods reduce waste. Wood’s lighter weight also cuts fuel use and emissions during transportation, particularly when sourced regionally. From a delivery standpoint, mass timber offers compelling schedule advantages. Prefabricated components, lighter assemblies, and the ability to sequence work in parallel can meaningfully shorten construction timelines, an increasingly important factor for clients who need projects delivered quickly and efficiently. Q: Detroit and the Midwest have long been defined by steel, concrete, and manufacturing. How does mass timber challenge or complement that legacy? A: Mass timber is highly complementary. Michigan was once the nation’s top lumber producer, giving the region a timber legacy that predates its steel and concrete era. At Gensler, we’re designing hybrid systems, such as Fifth + Tillery in Austin, that combine timber and steel to modernize existing structures. For each project, we partner with clients, engineers, and contractors to select the right system based on performance, sustainability goals, schedule, and budget. As mass timber gains momentum for its lower embodied carbon, it is also prompting steel and concrete industries to innovate and compete. Q: How do projects like the tall timber work featured at the MSU Tall Timber exhibit help shift conversations about what sustainable urban buildings can look like? The MSU Tall Timber exhibit, at Chrysler House (open until March, 2026), is a great way to broaden the conversation across the design and construction industries, real-estate community, property owners and the public on what is possible. The exhibit includes Gensler’s Proto-Model X project for Sidewalk Labs and mass timber projects from across the state. The curation team is also doing a great job of hosting events and panels that give project teams a chance to talk about projects and lessons learned. In legacy industrial cities, where we have a strong existing building inventory, we have a responsibility to preserve and repurpose our buildings. Nothing is more sustainable than reutilizing buildings and reducing waste, as seen with the Book Depository building in Corktown. For new buildings, we also have a responsibility to build for the future and make the best choices that we can with the materials at our disposal. Mass Timber is a responsible option and should always be considered. Q: Beyond sustainability, what design or human-scale qualities does mass timber introduce that more conventional materials often don’t? A: Wood brings a natural warmth and biophilic quality that supports wellbeing – lowering stress, improving cognitive function, and creating spaces that feel welcoming and calm. Exposing the structure adds authenticity and makes the architecture legible, helping people feel more grounded in the space. Q: What makes Michigan uniquely positioned to lead in mass timber and low-carbon construction? At the MSU Michigan Mass Timber Update in December, I was able to see the strength of the Michigan mass timber community coming together. The institutional leadership from Michigan State University and their director, Sandra Lupien, is positioning Michigan’s mass timber capabilities on a global level. Connections are being established across the market from – architects, structural engineers, MI EGLE, code officials, business and economic development associations, workforce training leaders to contractors and suppliers. Q: How could mass timber and life cycle thinking influence redevelopment in cities like Detroit, where adaptive reuse and reinvestment are central to the urban story? A: Detroit has led in adaptive reuse for over 25 years, proving that reinvesting in existing buildings delivers cultural, social, economic, and environmental value. Mass timber and lifecycle thinking are the next steps, offering lower carbon pathways as the city continues to grow. To make informed decisions, architects and clients need a full understanding of a material’s life cycle, from extraction and manufacturing to reuse and end of life. This is why circular economy thinking is so critical to future development. At Gensler, our Gensler Product Sustainability (GPS) Standards help guide this process by providing clear, industry-aligned criteria that accelerate the adoption of lower carbon materials in collaboration with the Common Materials Framework. Q: In a region shaped by reinvention, how do you see sustainable materials and measurement tools contributing to the next chapter of Detroit’s built environment? A: Detroit and Michigan have always thrived on reinvention. That same spirit of creativity positions the region to lead in the next wave of sustainable development. Our climate challenges, paired with the natural and industrial resources already here, create an ideal environment for adopting materials and strategies that will help Michigan thrive through future change. The growing investment in next-generation technologies is especially exciting. As industries across the state push toward innovation, there’s real potential for that momentum to drive broader adoption of low carbon materials, mass timber, and performance-based design tools. If we want to attract new residents, businesses, and industries, we need to shape buildings and public spaces that reflect where Detroit is going – healthy, efficient, resilient, and future focused. Q: As sustainability expectations continue to rise, what do you think will separate projects that genuinely reduce impact from those that simply meet minimum standards? Minimum standards are steadily improving as energy codes tighten and reduce allowable energy use, which means operational carbon is no longer the primary differentiator. What will set truly impactful projects apart is a commitment to addressing embodied carbon as well. Conducting Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) early in design gives clients and teams a clear baseline and empowers them to make more informed material choices. Projects that are serious about reducing their overall footprint will also look beyond efficiency to incorporate clean energy—whether by purchasing renewables from their utility or integrating onsite solutions. Michigan is particularly well-suited for ground source heat pumps, with stable underground temperatures that perform reliably through freezing winters and hot summers, and a strong network of engineers and installers who understand the technology. In short, the leaders will be the teams that measure comprehensively, design holistically, and pair low carbon materials

Urban Tech Xchange and Detroit Smart Parking Lab

Now in its fourth year of operation, Urban Tech Xchange (UTX) has become a living laboratory where emerging technology startups can test, refine, and validate smart urban systems in real-world conditions. Launched through a collaboration between Bedrock, Bosch, Cisco, and Kode Labs, UTX builds on the foundation of the Detroit Smart Parking Lab (founded earlier by Bedrock, Ford, MEDC, and Bosch) expanding its scope beyond parking into logistics, energy, building automation, accessibility, and freshwater tech. What differentiates UTX from other technology incubators and accelerators is its emphasis on real-world deployment. Rather than testing concepts in isolation, startups pilot technologies directly within Detroit’s streets, curbsides, buildings, and rooftops, allowing solutions to be measured against real constraints such as emissions reduction, infrastructure utilization, and resident impact. Over the past four years, that approach has helped deploy dozens of pilots and move some into active use. SBN Detroit interviewed Kevin Mull, Bedrock’s Senior Director for Strategic Initiatives, about how Southeast Michigan’s legacy industries are shaping the next era of sustainable urban logistics—and how incremental efficiencies can deliver meaningful environmental gains at city scale. Q: What factors help position Southeast Michigan to rethink how urban logistics can improve daily life in cities like Detroit? A: Southeast Michigan has been designing, building, and deploying mobility solutions for generations. What’s different right now is that we’re at a special moment where the relationships, the talent, and the physical space all align. We have room to test ideas, and we have strong public-private partnerships that allow us to deploy technology. Bedrock’s Detroit Smart Parking Lab (DSPL) and Urban Tech Xchange (UTX) give startups the ability to move beyond theory. Through platforms like the Michigan Mobility Funding Platform, we’ve been able to deploy a million dollars in grants to early-stage companies tackling real logistics and mobility challenges. Over the past four years, several of those pilots have become production-ready solutions now operating across Detroit—from curbside EV charging to streetlight-mounted charging systems. Q: How do wasted miles, underused infrastructure, or inefficient logistics affect urban environments and quality of life? A: Wasted miles translate directly into congestion, emissions, and frustration. Vehicles circling for parking, trucks idling in residential areas, or delivery vehicles double-parking because curb space isn’t managed well—all of that erodes the day-to-day experience of a city. Underutilized infrastructure is another big issue. Curbsides, loading zones, rooftops—these are valuable assets that often aren’t managed intentionally. At Bedrock alone, we process roughly 100,000 parking transactions per month. Every single one of those transactions is an opportunity to reduce friction or create value. We are focusing on solutions that remove friction. One example is IONDynamics, that’s working on automated EV charging. Another is HEVO – a wireless charging solution. Small improvements, repeated thousands of times, add up quickly. Q: How do smarter logistics systems change the way residents experience sustainability day to day? A: Sustainability becomes tangible when it improves daily life. Fewer vehicles circling means cleaner air and quieter streets. Better-managed loading zones mean safer sidewalks. More predictable deliveries mean less congestion during peak hours. One pilot we ran used a small autonomous robot to transport food scraps between restaurants and upcycling locations. Over the course of that project, it diverted more than 2,600 pounds of food waste and eliminated nearly 1,200 pounds of greenhouse gas emissions by replacing traditional vehicle trips. It also avoided the use of about 56 gallons of fuel. Those numbers matter, but what residents notice is the absence of friction—less noise, less traffic, and fewer large vehicles in tight residential spaces. Sustainability works best when it’s embedded into systems people already rely on. Q: How can improved last-mile logistics help reduce unnecessary driving and strengthen neighborhood connectivity? A: The last mile is one of the most important parts of the logistics chain and is often the most inefficient. A lot of energy is going into that space right now because it has outsized impact. Better coordination of curb space, smarter delivery scheduling, and multimodal solutions all reduce the need for unnecessary trips. When people can reliably park, receive deliveries, or access transit without friction, neighborhoods become more functional and connected. We focus on the edges—where parking garages meet transit, where delivery vehicles meet sidewalks, where people move between modes. Improving those interfaces creates meaningful gains without massive infrastructure investments. Q: Many of the technologies supported by UTX reduce congestion and emissions. How do you think about sustainability in this work? A: Sustainability is an outcome of better systems rather than the starting point. When you reduce wasted miles, idle time, and inefficient use of infrastructure, the environmental benefits follow naturally. If we can take miles off the street, shorten dwell times, or make curb space and parking more productive, we reduce emissions without asking people to change their behaviors. Across the Bedrock portfolio, we also think a lot about avoided infrastructure. For example, we’re exploring automated valet parking technology start-ups that aim to allow cars to park closer together and improve garage efficiency by an estimated 20 percent. That can delay—or eliminate—the need to build new parking structures, which has a significant embodied carbon impact. Another example is an automated robot charging solution from Ion Dynamics, which has a charging robot move to the vehicles require charging, which is a dynamic solution that avoids adding costly fixed charging infrastructure. The same logic applies to delivery drones, ground-based robots, and micro-mobility. Moving packages through the air or via small electric vehicles instead of gas-powered trucks reduces fuel consumption and congestion. Q: Where do you see the biggest opportunities for Southeast Michigan cities to improve logistics in ways that benefit both residents and businesses? A: The opportunities are everywhere, but they’re often measured in inches rather than miles. Smarter curbside management. Better coordination between delivery systems and transit hubs. More efficient use of shared infrastructure. Individually, these improvements may seem small. But in the aggregate, they have outsized impact. Through platforms like UTX and DSPL, we’re helping startups test those ideas, refine them, and scale what

Navigating Environmental Compliance

Butzel is one of Michigan’s longest-standing law firms, advising businesses across industries on regulatory compliance, environmental law, and complex commercial matters. As environmental expectations evolve alongside shifting regulatory realities, the firm plays a key role in helping companies navigate both legacy challenges and emerging risks. SBN Detroit interviewed Butzel shareholder Beth Gotthelf to discuss how environmental compliance, sustainability, and innovation are intersecting today — particularly in Southeast Michigan — and what businesses should be paying attention to in the years ahead. Q: From your perspective, what are the most consequential changes shaping how companies approach compliance and sustainability today? A: Many companies still treat compliance and sustainability as separate conversations. Compliance is something they aim for while sustainability is framed as an aspirational goal. Where those two intersect most often is when sustainability also makes business sense. Reducing water use, reusing materials, and improving efficiency often lower costs. Recycling and waste reduction can improve margins. As a result, many organizations are approaching sustainability less as a branding exercise and more as a fiscal and operational strategy. Q: How are businesses navigating the tension between accelerating sustainability goals and increasingly complex regulatory frameworks at the state and federal levels? A: Right now, I don’t see the same level of tension that existed a year or two ago, particularly in Michigan, unless they also have facilities outside of the U.S. or in California. Many companies still believe in climate action and sustainability, but they’re not always using that language domestically given the current federal environment. That said, sustainability reporting is mandated outside the US, with the European Union leading the way for larger firms, and nations like Australia, China, India, and Japan requiring disclosures. Those requirements still apply across all divisions, including U.S. facilities. One area where regulatory complexity is very real is battery recycling, particularly lithium batteries. The regulatory framework in the U.S. makes recycling more difficult than in other countries. That’s an area where we need better alignment to compete in the global market. There is progress happening, but it remains a challenge. Q: Southeast Michigan has a deep industrial legacy alongside growing environmental expectations. What challenges does that history create for remediation and compliance in this region? A: There are many. One challenge, for example, is that materials historically considered “clean fill” may no longer be viewed that way under current standards. The question becomes: do we excavate and remove it all? That creates dust for the area, truck traffic, emissions, road wear, and additional environmental impacts. In some cases, the net environmental benefit is questionable. We also face decisions around highly contaminated sites — whether to cap and manage contamination in place or attempt full remediation to pre-industrial conditions, which can be extremely costly and disruptive. I have simplified the issue but there is a balance between the desire to re-use contaminated sites (brownfield), finding a new productive use, and moving to a ‘greenfield,’ where you do not have to incur the cost, time, and worry of a brownfield. On the compliance side, Southeast Michigan has dense industrial areas adjacent to residential neighborhoods, particularly in places like Southwest Detroit. That proximity creates ongoing tension between maintaining industrial activity and protecting air quality and public health. These are not simple issues, and they require balance rather than absolutes. Q: Are you seeing a shift from reactive environmental compliance to more proactive strategies? A: Yes, overall companies are more proactive than they were decades ago. There’s greater environmental stewardship and awareness. There are better tools to allow for reuse, recycling, lower emissions, fewer chemicals being discharged in wastewater, better management of stormwater, etc. Companies are constantly looking and then implementing those tools. People, whether a resident, employee, or both–want products that last, clean water for swimming and boating, and healthy ecosystems — and they also want manufacturing and economic growth. Balancing those priorities is ongoing but can be done. We can build manufacturing and provide jobs while protecting the environment. Larger companies tend to have more resources to implement sustainability strategies and work with suppliers to raise standards. That said, the last year has been different. Incentives to pursue sustainability have diminished, and in some cases, companies feel penalized for investing in these efforts. That has slowed momentum for some organizations. Q: What role does innovation play in helping companies meet environmental obligations without stalling growth? A: Innovation is essential. It shows up in many forms — energy management software, automation, detection systems, improved chemicals, safer materials, and better protective equipment to name a few. There’s also a real opportunity to expand access to innovation, especially for small and midsize companies. More forums, education, and exposure to tools like energy tracking, water reuse, stormwater management, and greywater systems would help accelerate adoption. Innovation should be encouraged, not siloed. Q: How are climate-related risks influencing environmental decision-making in the Great Lakes region? A: Water quality has become a major concern. The Flint water crisis highlighted how municipal systems directly affect not just residential, but industrial operations. Poor water quality can damage equipment and disrupt production, forcing companies to install additional filtration and safeguards. Flooding is another growing issue. We’re seeing more frequent and severe rain events, impacting facilities across urban and rural areas alike. It is not good when a facility is flooded, potentially allowing chemicals to flow into the environment or causing work to stop. There are a variety of causes of flooding, some related to the drainage system on property, and some off property. Managing flood risk increasingly requires coordination between municipalities and private operators. Extreme weather — snow, wind, heat, flooding — is becoming part of long-term planning. Some larger companies are building redundancy across regions, but many Michigan businesses are smaller and must do the best they can within limited resources. Q: Compared to other regions, what opportunities does Southeast Michigan offer for sustainable redevelopment and clean manufacturing? A: Southeast Michigan has an abundance of industrial sites suitable for adaptive reuse, along with a strong workforce

Strengthening Michigan’s Ecosystems

Pollinators are essential to Michigan’s ecosystems, food systems, and long-term environmental resilience — yet they face increasing threats from habitat loss, pesticides, disease, and climate change. As Southeast Michigan looks for scalable, science-based approaches to ecological stewardship, the University of Michigan-Dearborn has emerged as a voice in pollinator conservation, sustainability, and community education. SBN Detroit interviewed Dr. David Susko, Associate Professor of Biology and Chair of Biology in the Department of Natural Sciences at UM-Dearborn, about the university’s Bee Campus USA affiliation, the initiatives underway on and beyond campus, and why the region is positioned to advance pollinator health. Q: What role does Bee Campus USA play at UM-Dearborn? A: First, it’s important to distinguish Bee City USA from Bee Campus USA. They share a common mission, but Bee Campus USA focuses specifically on higher education institutions. Both programs create a national framework — and a third-party certification — that helps cities and campuses advance pollinator education, habitat management, and long-term preservation. For us, the affiliation established a baseline. It gave us a structured way to track what we were already doing, identify gaps, and strengthen our commitment to pollinator health. It also connects us to a national network so we can benchmark progress, share strategies, and stay accountable. In many ways, it formalized work that had been happening here for decades. Q: What concrete steps has the university taken to support pollinator health, biodiversity, and sustainable landscapes? A: Many of our efforts predate the certification. UM-Dearborn has had an organic community garden since the 1970s and a strong environmental stewardship culture. Since I joined the campus in 2003, we’ve expanded those efforts significantly. We’ve added pollinator gardens and rain gardens, managed a campus bee yard for several years, and partnered closely with our facilities and grounds teams. They’ve been instrumental — reducing pesticide use, transitioning to organic fertilizers, and designating additional “no-mow” or naturalized areas on campus. These provide habitat for insects, reduce emissions from mowing, lower maintenance costs, and support overall soil and ecosystem health. Q: What challenges have you encountered in implementing pollinator-friendly landscapes? A: The biggest challenge is cultural. People often equate “well-maintained” with “closely mowed.” A pollinator-friendly landscape looks different — and sometimes that difference requires explanation. These spaces aren’t unkempt; they’re functioning ecosystems. Naturalized areas improve biodiversity, reduce fertilizer use, cut emissions, and support wildlife. Part of our work is helping people reframe what beauty looks like in a sustainable landscape. Once they understand the ecological benefits, they usually become strong supporters. Q: How are students, faculty, and staff involved in these initiatives and what types of engagement have you seen? A: Engagement is one of our greatest strengths. The Environmental Interpretive Center (EIC), which opened in 2001, draws thousands of visitors each year for free programming related to ecology, natural history, and pollinators. We host workshops, seasonal programs, and young naturalist sessions. These opportunities reach not only students, but families, K-12 classes, and community members. We also offer volunteer stewardship events — “Stewardship Saturdays” — where participants help remove invasive species and restore habitat quality. These have become incredibly popular. And at an academic level, pollinator initiatives are woven into coursework, research, and capstone projects. For many students, this becomes their first real stewardship experience. They see how their work directly contributes to the regional ecosystem and realize the role they can play in addressing pollinator decline. Q: Can you share an example of how sustainability and pollinator conservation intersect with experiential learning or research on campus? A: A great example is the PolliNation Project, which began when a student approached me wanting to take more action. Ultimately, this became a campus and community-wide initiative to build insect hotels in order to promote pollinator awareness and conservation. Insect hotels are like birdhouses for pollinators. Our students built and distributed roughly 250 of these hotels across the region. We worked with the College of Engineering and Computer Science, part of which is a design course where students develop apps for real-world stakeholders. The students ended up creating two digital tools: the PolliNation ID App, which helps users identify species, and the PolliNation Hotel App, which tracks locations and resources for “insect hotels.” The project earned a Ford College Community Challenge (C3) Grant and inspired broader outreach. Rescue Michigan Nature Now donated additional hotels, and our apps and online materials help residents build their own. This is what experiential sustainability education should look like — students creating tools with real ecological and community impact. Q: What value do these efforts bring beyond the campus borders, especially to Detroit-area communities? A: Our work extends into the region in several ways. The PolliNation Project has been integrated into the Rouge River Gateway Trail through interpretive signage, giving visitors a deeper understanding of pollinators. Our online resources help residents and community groups design their own pollinator habitats. We also collaborate with Detroit-based partners. For example, the Dearborn Shines initiative brings schoolyard gardens — including pollinator beds — to local schools. Students learn about nutrition, ecology, and pollinators simultaneously. UM-Dearborn students helped design and build these spaces, creating a powerful feedback loop of education, stewardship, and hands-on impact. Q: Detroit and Southeast Michigan have a unique ecological and urban history. Why is Bee Campus designation meaningful here? A: This region carries both ecological richness and environmental challenges. We have hundreds of native bee species in Michigan alone, many of which rely on the exact types of habitats we’re restoring. At the same time, urbanization and habitat fragmentation make pollinator conservation more urgent. Being a Bee Campus in this context means modeling what sustainable land stewardship looks like in a northern, urbanized ecosystem — and showing that cities and campuses can play a leadership role in ecological recovery. Q: What challenges and opportunities does Southeast Michigan’s climate present for pollinator protection? A: Overwintering is a major issue. Honeybees struggle in northern climates, and climate variability makes conditions more unpredictable. Beekeepers in Southeast Michigan are experimenting with improved insulation techniques

Preparing for the AI Energy Era

ThermoVerse is a Detroit-based urban innovation startup founded by engineer and researcher Shantonio Birch. The company’s work centers on advanced thermal energy storage and people-focused building technologies that reduce waste, stabilize indoor environments, and free up electrical capacity. SBN Detroit interviewed Birch about the future of grid resiliency, energy equity, and why Southeast Michigan is positioned to lead in next-generation smart city innovation. Q: What is the impetus behind the work you do? A: ThermoVerse is focused on one of the biggest stability issues we face: how do we allow high-energy users like data centers to coexist in communities without competing for the same energy we need to heat homes and businesses? Our goal is to reduce the largest source of energy consumption in buildings — the HVAC system — so more energy is available at the panel. We want to empower building owners to turn their buildings into value-added assets instead of liabilities. Q: What are the biggest challenges buildings face? A: It all comes down to energy. There are many issues in the built environment, and I think of buildings like the human body — everything is connected. We talk about indoor air quality and comfort, but when you look at economic development, the thing that will get this nation moving is our relationship to energy. Right now, poor power quality is being distributed through the grid and into homes, affecting how our devices and systems function. When you layer on additional demand from advanced manufacturing, EVs, and AI data centers, we’re going to experience more brownouts and blackouts. That’s the biggest challenge buildings are facing: how do we allow this huge economic wave — fueled by AI — without compromising communities? Q: What technologies or approaches will have the greatest impact on reducing energy waste in buildings? A: Anything simple. The biggest barrier for new technology is integration, so solutions have to be straightforward. I believe thermal energy storage is a major opportunity. It will play a huge role in meeting grid-resiliency needs. Renewables like solar are valuable, but they don’t solve the smart-growth challenge we face. We need growth that strengthens the grid rather than stressing it. Q: How does better thermal management translate into healthier or safer living conditions? A: I found my way into this field because I experienced heat stress in my own townhouse apartment during the pandemic while studying at U-M. I was close to heat stroke. We’re seeing more and more cases of heat stress in hospitals and communities now. Better thermal management helps reduce those risks. Beyond the health impact, there’s the economic side. Many people are spending a significant portion of their income on utilities. Improved thermal performance means lower bills, better living conditions, and more resilience as heat waves become more frequent. Q: What role can innovation play in addressing energy inequity — especially in aging housing stock and low-income communities? A: I’ll say this boldly: most existing building technologies were not designed with equity or people in mind. They were built around the question, “How do we cool this space so we can have people here?” At ThermoVerse, we flip that script. We build around the people first. People-centric technologies will play a huge role in reducing energy demand and supporting smart growth so AI and other advancements can coexist with communities instead of overwhelming them. Q: What makes Southeast Michigan a meaningful place to build and test smart-city and energy-efficiency technologies? A: If you look at major cities like Chicago or New York, Detroit stands out. We have the greatest potential for smart-city innovation because our built environment is underdeveloped in certain areas, making the starting point ideal. We can embed smart infrastructure into buildings more easily to enable fluid energy transfer between the grid and the built environment. There’s also a level of openness and willingness here that you don’t always find in cities that are already fully built out. Q: What barriers still slow down the adoption of innovative building technologies, even when they’re proven to reduce waste? A: Integration. That is the barrier for most proven technologies. We also have split incentives in the built environment. Building owners are our customers, but their customers — the tenants — want a better user experience. Then you have utilities, with power-purchase agreements and rate structures that complicate adding new technologies. And finally, the contractors. They’re the ones installing the equipment. If they don’t understand how a new technology fits into existing systems, it won’t be integrated. Heat pumps are a good example — contractor knowledge gaps can slow down adoption, even when the technology is solid. Q: For building owners looking to modernize, where should they focus first to get the biggest energy impact? A: If you’re going to modernize, you have to measure. Establish a baseline. Invest in sensors and meters to understand your energy use down to the unit. You can’t manage what you don’t measure. Once you have visibility, you can start thinking about the ecosystem of technologies that will create the biggest short-term and long-term impact. Ultimately, we need buildings — and neighborhoods — where energy flows bi-directionally between the grid and the built environment. Q: Looking ahead, what do you believe will define the next chapter of energy innovation in Detroit and more broadly? A: Detroit has a deep understanding of how communities and businesses coexist. The next evolution of the built environment here will be people-based — designed around the experience of living and working well. Nationally, we’re at a very interesting moment in energy. For years, the “energy transition” has been politicized, and we’re now looking at it through an economic lens driven by AI. The biggest opportunity ahead is doubling our energy production to meet the demands of AI data centers. The White House recently launched the Genesis Mission — the largest investment in strengthening our national energy reserve to prepare for the new digital era. There’s an enormous opportunity for young people to enter this