Building More Sustainable Homes Through Automation

Citizen Robotics is a Detroit-based nonprofit that advances the use of robotics and digital manufacturing in residential construction, focusing on improving productivity, sustainability, and long-term affordability. Best known for its early work in 3D-printed housing, it explores how alternative construction methods and new financial models can reduce material waste, lower lifetime operating costs, and enhance the resilience of homes. SBN Detroit interviewed Tom Woodman, founder and president of Citizen Robotics, about why housing has lagged behind other industries in adopting new technologies, the structural barriers facing innovative construction methods, and what it would take for models like 3D-printed housing to move from experimentation to scale. Q: Tell me about Citizen Robotics and the impetus behind it. A: The homebuilding industry largely missed the digital revolution. Productivity has been flat for decades and, that has directly contributed to the rising cost of new construction. It has also limited progress on sustainability, from material efficiency to energy performance. At the same time, the industry has struggled to attract younger workers, in part because it’s perceived as manual and outdated. Citizen Robotics was formed in response to that dynamic. The idea was to demonstrate that a robotic future for homebuilding is not only possible, but achievable now. We centered our early work on 3D construction printing because it brings together robotics, digital design, and material innovation in a way that could fundamentally change how homes are built. Q: Citizen Robotics drew early attention for its work in 3D-printed housing. Where is the organization today? A: That early work generated a lot of interest from the community and the media. One of the most important outcomes was that people could physically experience the technology. Thousands of people toured the house, touched it, walked through it, and asked questions. You could see perceptions shift once people understood what was actually possible. Today, we’re working more directly with municipalities and partners to move toward a structure that can support real-world deployment. We’re exploring a for-profit framework that would allow 3D printing to achieve broader impact, including a model we call “Build for Equity,” which combines rental housing with shared equity over time. Q: In your experience, what are the biggest barriers to scaling new housing technologies like 3D printing? A: Many people assume the barrier is more innovation — better robots, better materials. In reality, we’ve shown that even existing robotic systems can deliver meaningful gains, not only in productivity but in material efficiency and long-term performance. The real barriers fall into four areas: market acceptance, continuity of capital, industry conservatism, and a funding gap around productivity. Housing is expensive no matter how it’s built, and resale value is always top of mind. Anything outside the mainstream creates anxiety for buyers, lenders, and developers. Sustainability benefits, such as durability, resilience, and lower operating costs, are rarely reflected in how homes are valued or financed, which makes adoption harder. There’s also a Catch-22. To make homes cheaper, you need volume and repetition. But to get volume, you need lenders to underwrite projects, and they need comparable data that doesn’t yet exist. Q: Why has housing been so slow to adopt automation compared to other industries? A: A big part of it comes down to incentives. Construction largely delivers what the system pays for. The way homes are financed, maintained, and insured often works against affordability over the long term. If we want healthier, more durable homes, we need to reward innovation rather than cost-cutting that degrades quality. Right now, the system works well for those already positioned to profit from it. Changing outcomes requires changing incentives. Q: From your vantage point, where is the greatest opportunity to rethink how homes are built? A: One of the biggest opportunities is Detroit’s inventory of residential lots, combined with a different financial model paired with industrialized construction methods. Build for Equity is about constructing homes for rent while allowing renters to build equity over time through a shared fund structure. That model allows us to focus on the total cost of ownership. From a sustainability standpoint, materials like concrete offer fire, flood, and storm resilience, along with lower long-term maintenance and operating costs. When homes are evaluated based on total cost of ownership — including energy use and durability — innovation becomes much easier to justify. Q: What does it take to keep an innovation-focused organization viable during periods of uncertainty? A: It’s difficult, particularly in a challenging fundraising environment. But the need hasn’t gone away. Around the world, 3D construction printing is advancing – in Texas, Florida, Ontario, Kenya, Japan, and beyond. We learn from those efforts and adapt what makes sense locally. The key is securing capital for repeatable projects so the technology can move beyond prototypes and generate the data lenders need. Q: What would meaningful progress look like for Citizen Robotics over the next few years? A: Moving from prototypes to a repeatable playbook that lenders are comfortable underwriting. Training and placing at least 60 workers into high-tech construction roles. Scaling projects across multiple municipalities. Michigan has the ingredients to become a proving ground for innovative and more sustainable construction, from advanced manufacturing expertise to policy interest in sustainability. The challenge is unlocking the first wave of projects. Q: What needs to change for innovative housing models to become permanent? A: We need financing structures that optimize for total cost of ownership, not just upfront cost. Philanthropy can play a role in de-risking early projects and funding workforce development. Policy matters too. Zoning reform, incentives for net-zero housing, and support for local job creation all help create space for innovation. With the right mix of public, private, and philanthropic investment, we can keep jobs local, improve housing quality, and move toward a more sustainable construction system. Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on sustainable business practices in and around Detroit.

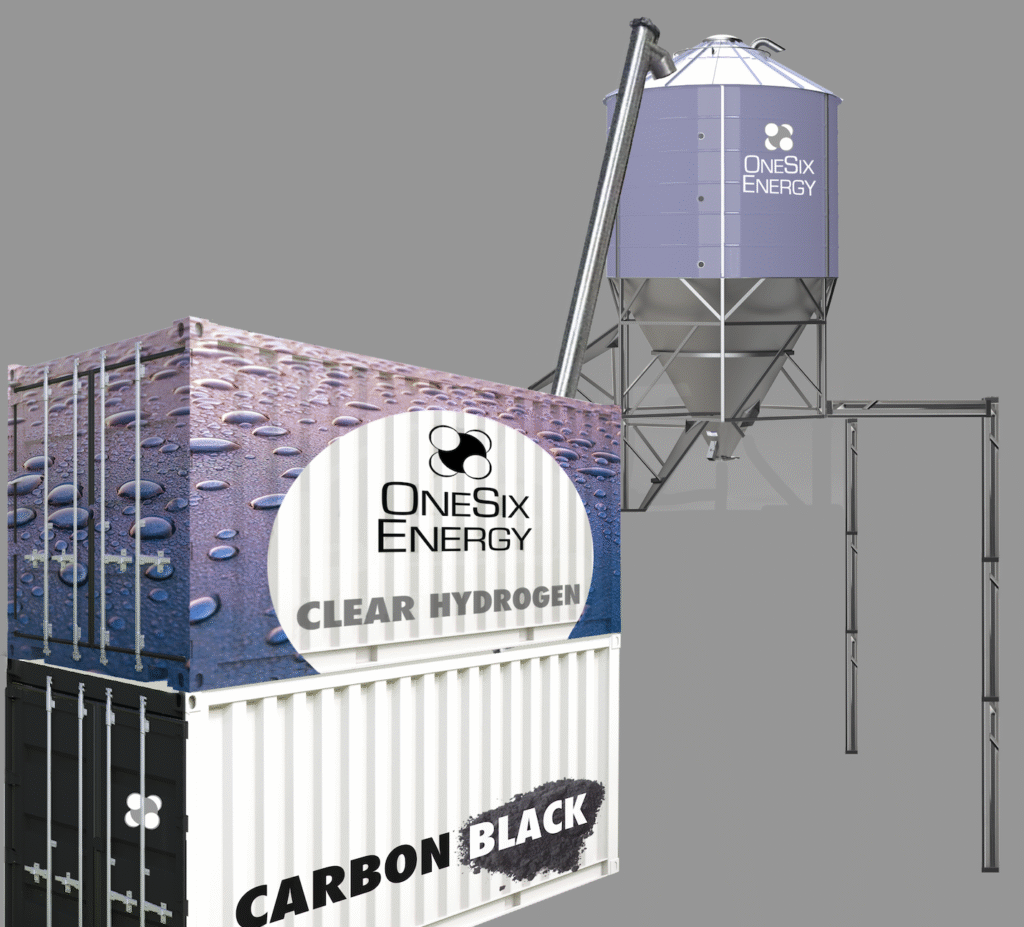

Rethinking Hydrogen Production

Detroit-based OneSix Energy is a clean-energy technology company focused on advancing a lower-carbon approach to hydrogen production. Headquartered at Newlab in Detroit, the startup is developing a proprietary methane pyrolysis system designed to produce hydrogen without carbon dioxide emissions, while also generating solid carbon as a co-product. SBN Detroit interviewed with cofounder Stefan Sysko about the company’s origins, its approach to hydrogen production, and why Detroit is positioned to play a leading role in the next phase of the energy transition. Q: Can you give us the elevator version of OneSix Energy — how it got started, the impetus behind it, and the approach you’re taking to hydrogen production? A: OneSix Energy really began with my co-founder, Dan Darga, who back in 2002 was working at General Motors. He read about the hydrogen economy and immediately knew he wanted to be part of it. He transferred to GM’s fuel cell division in upstate New York, then later worked for a solid oxide fuel cell company. While there, he kept running into the same problem: carbon buildup clogging systems. His perspective was that we were fighting nature instead of working with it. That led him to start thinking differently about surfaces, materials, and how carbon behaves. Dan eventually left to work at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he learned how to take ideas from concept to deployment in extreme, real-world conditions. He combined these two experiences, refined them, and approached me. I’ve been a lifelong entrepreneur, and I felt I had one more startup in me — one that could genuinely address a major global challenge. We incorporated OneSix Energy nearly two years ago, bootstrapped the initial design and modeling, filed a patent that’s now pending, raised a friends-and-family round, built and independently tested a prototype, and are now moving toward a pilot phase. Q: What problem is hydrogen uniquely positioned to solve that other energy carriers can’t? A: Hydrogen is incredibly energy-dense by mass, and when it’s used, the only byproduct is water vapor. It’s versatile — it can be used as a fuel for power generation or as a chemical feedstock. Hydrogen has been called “the fuel of the future” for decades but it’s difficult and expensive to produce cleanly. Today, about 90 percent of hydrogen is made using steam methane reformation, which is cheap but very dirty — roughly 11 tons of CO₂ for every ton of hydrogen produced. Electrolysis, on the other hand, is clean but extremely expensive and water-intensive. It requires fresh water, significant electricity, and even when powered by renewables, you lose about half the energy in the process. When you look at sectors like data centers — which already consume enormous amounts of electricity and water — electrolysis actually worsens the problem. Our system is different. We’re off-grid. We recirculate a fraction of the hydrogen we produce to power our reactor, so we don’t need external energy, and we don’t use water. In fact, we generate fresh water as a byproduct. Q: Can you explain methane pyrolysis and what OneSix Energy has developed? A: Methane pyrolysis involves taking methane — CH₄, the main component of natural gas — and breaking it into hydrogen and carbon using high temperatures in the absence of oxygen. Because there’s no oxygen, you don’t form CO₂. Instead, you produce solid carbon. That solid carbon – or “carbon black” – is actually valuable. It’s used in products like tires, shoe soles, and industrial materials. There’s a roughly $40 billion global market for carbon black today. Our goal is to upcycle that carbon while producing hydrogen at a lower cost than electrolysis, without water use or external energy input. Q: Hydrogen production often involves trade-offs. What innovations are helping overcome those barriers? A: Right now, the industry is stuck between options that are either cheap and dirty or clean and expensive. What’s changing is the recognition that we need new pathways — not just incremental improvements. Innovations in materials science, reactor design, and system efficiency are making approaches like methane pyrolysis viable at scale. The key is eliminating emissions without introducing new resource constraints. Q: Where do you see the earliest and most impactful applications for clean hydrogen? A: Two areas stand out immediately: data centers and shipping ports. Ports face increasing regulatory pressure because of emissions from ships idling while docked. Hydrogen-powered equipment and shore power could significantly reduce pollution while keeping operations moving. We also see opportunities in power generation for buildings, factories, and industrial facilities. Long-term, hydrogen fuel for heavy-duty transportation — Class 8 trucks, for example — is very compelling. Electrifying those vehicles requires massive and expensive batteries that reduce payload capacity. Hydrogen avoids that issue. Q: Why build a clean-energy technology company in Detroit? A: Detroit put the world on wheels. There’s no reason it shouldn’t lead the energy transformation. We’re at Newlab, surrounded by engineers, manufacturers, and people who understand how to scale physical systems. Detroit is a perfect microcosm — a place where you could demonstrate how an entire city transitions to clean energy. Plus, I was born and raised in the city, so it’s home to me. Q: What misconceptions do you encounter most often about hydrogen? A: The first is safety. People immediately think of the Hindenburg. But hydrogen is actually lighter than air and dissipates quickly, whereas gasoline fumes stay low and linger. When you look at safety data, hydrogen performs very well compared to other fuels. The Hindenburg taught us the hard way that we need to develop unique handling procedures for hydrogen – and we have. Q: What should Michiganders understand about hydrogen’s role in a sustainable energy future? A: Michigan potentially has significant natural hydrogen resources, which should be explored. But we need to remember that it will likely be years, if not decades, before that becomes viable, We also have the Great Lakes — which must be protected. If all hydrogen today were produced via electrolysis, the water consumed would be equivalent to Lake St. Clair

Inside Michigan’s Environmental Justice Landscape

Regina Strong serves as Michigan’s first Environmental Justice Public Advocate, leading the state’s Office of the Environmental Justice Public Advocate. Her role focuses on addressing environmental justice concerns raised by communities, helping residents navigate environmental systems, and working across state agencies to improve equity in environmental decision-making. SBN Detroit interviewed Strong about the challenges communities are facing across Michigan and what environmental justice work looks like in practice. Q: As Environmental Justice Public Advocate, what does your work look like day to day? A: There really is no typical day. This role was created to address environmental justice concerns and complaints, to advocate for equity, and to help communities navigate systems that can feel opaque or inaccessible. That can mean many things. On a given day, I might be working on our Environmental Justice Screening Tool as we migrate it to a new platform, meeting with one of our 43 grantees across the state, or sitting down with other state departments or divisions within EGLE, where my office is housed. Other days are spent directly with community members – listening to concerns, helping them understand what levers exist, and figuring out how to move forward. The work ebbs and flows depending on what’s happening in communities. Over the past seven years, we’ve seen some issues emerge seasonally, in response to new development, extreme weather, or long-standing infrastructure issues. Ultimately, my work is deeply relational and constantly evolving. Q: What are the most pressing environmental justice issues you’re hearing across Michigan and how do they differ between urban, suburban, and rural communities? A: There’s actually a lot of overlap across geographies. Whether people live in dense urban neighborhoods, suburban communities, or rural areas, we consistently hear concerns about water – lead service lines, contaminated wells in rural areas, and flooding. Air quality is another major issue, especially near industrial corridors or transportation infrastructure. In more densely populated areas, concerns often cluster around industry, waste facilities, landfills, and cumulative air pollution. In rural areas, it may be wells, septic systems, or access to clean drinking water. Across all regions, energy burden comes up frequently, particularly during winter months, when households are forced to spend a disproportionate share of income on utilities. Climate change is amplifying many of these issues. Flooding, power outages, and extreme weather events are becoming more common, and their impacts are not evenly distributed. The underlying issues may differ by location, but the throughline is vulnerability tied to infrastructure, income, and exposure. Q: What are the hardest gaps to close when translating community concerns into action? A: One of the biggest challenges is that environmental justice issues rarely fall under a single authority. A concern may involve state permitting, local zoning, county health departments, and federal regulations all at once. Our office often helps communities navigate those layers. From an environmental justice perspective, equitable access to decision-making is critical. We work to ensure voices are heard, especially in communities that have historically been underserved. We do a lot of resilience planning in – for example – the 48217 ZIP code (Southwest Detroit) in the heart of a very dense industrial corridor. We also work with communities near hazardous waste facilities and communities with drinking water concerns. Many of these challenges have deep historical roots. Our role is often about helping communities access resources, understand processes, and advocate effectively while acknowledging that solutions are rarely immediate, yet possible. Q: To that end, how does history complicate environmental justice work today? A: History matters a great deal. Many environmental regulations around air and water are set at the federal level and applied category by category. Communities, however, experience impacts cumulatively – air, water, land use, and health intersecting in daily life. That mismatch creates tension. Residents want holistic solutions, but regulatory frameworks don’t always account for cumulative impacts. Before the Clean Air Act and Safe Drinking Water Act, people lived near industrial facilities for decades – and still do. Laws have improved, but legacy exposure and infrastructure decisions remain. Balancing regulatory constraints with community realities is one of the most complex aspects of this work. Q: What structural or systemic barriers are hardest to change? A: Policy is often written within narrow frameworks that don’t always center people’s lived experiences. That’s a persistent barrier. Another is data – how it’s collected, interpreted, and applied. MI EJ Screen, the state’s environmental justice screening tool is designed to help address that gap. It looks at environmental conditions, demographics, and health indicators together, creating a shared reference point for communities, government, and industry. The first version was launched in 2024, and expanding its usability is a priority because shared data helps align conversations and advocacy. Understanding how existing laws interact and where they fall short remains both a challenge and an opportunity. Q: How has your background in clean energy advocacy and community development shaped your approach? A: Where you live often determines the challenges you face. Working in community development and later in clean energy made that clear. Lower-income communities and communities of color are more likely to experience environmental burdens, often due to proximity to industry or aging infrastructure. That perspective informs everything I do. Some issues can be addressed through regulation, but others require working directly with communities to improve daily quality of life. Our Environmental Justice Impact Grant Program is one example – 43 grants statewide, including many in Detroit, supporting grassroots organizations, schools and communities addressing local concerns. This office sits outside of regulatory enforcement, which allows us to take a broader, more human-centered view. Q: How do you think about progress for residents living with impacts right now? A: Progress can look small but be very meaningful. Having a dedicated office focused on environmental justice is progress. Having tools that didn’t exist before is progress. If progress means a senior is no longer dealing with basement flooding because they received support for a sump pump, that matters. We have to focus on both micro-level quality-of-life improvements and

Building the Next Generation of Urban Infrastructure

Founded in 1965, Gensler is a global architecture and design firm working across sectors including urban development, commercial real estate, and civic infrastructure. SBN Detroit sat down with Najahyia Chinchilla, senior associate and sustainability consultant, to discuss mass timber, embodied carbon, and what sustainable construction means for Southeast Michigan. Q: Why is wood re-emerging right now as a serious option for large-scale, urban construction? A: Mass timber blends strength, sustainability, and design quality in ways few materials can. Wood has been used for centuries, but today’s engineered timber products – CLT, glulam, DLT, and NLT – bring a new level of precision, consistency, and performance that aligns with modern building requirements, including strict quality control and predictable fire resistance. Another driver is the industry’s increasing focus on reducing embodied carbon. Compared to steel and concrete structural systems, mass timber can significantly lower a project’s carbon footprint. At the same time, sustainably managed forests contribute to carbon sequestration and biodiversity, while modern processing methods reduce waste. Wood’s lighter weight also cuts fuel use and emissions during transportation, particularly when sourced regionally. From a delivery standpoint, mass timber offers compelling schedule advantages. Prefabricated components, lighter assemblies, and the ability to sequence work in parallel can meaningfully shorten construction timelines, an increasingly important factor for clients who need projects delivered quickly and efficiently. Q: Detroit and the Midwest have long been defined by steel, concrete, and manufacturing. How does mass timber challenge or complement that legacy? A: Mass timber is highly complementary. Michigan was once the nation’s top lumber producer, giving the region a timber legacy that predates its steel and concrete era. At Gensler, we’re designing hybrid systems, such as Fifth + Tillery in Austin, that combine timber and steel to modernize existing structures. For each project, we partner with clients, engineers, and contractors to select the right system based on performance, sustainability goals, schedule, and budget. As mass timber gains momentum for its lower embodied carbon, it is also prompting steel and concrete industries to innovate and compete. Q: How do projects like the tall timber work featured at the MSU Tall Timber exhibit help shift conversations about what sustainable urban buildings can look like? The MSU Tall Timber exhibit, at Chrysler House (open until March, 2026), is a great way to broaden the conversation across the design and construction industries, real-estate community, property owners and the public on what is possible. The exhibit includes Gensler’s Proto-Model X project for Sidewalk Labs and mass timber projects from across the state. The curation team is also doing a great job of hosting events and panels that give project teams a chance to talk about projects and lessons learned. In legacy industrial cities, where we have a strong existing building inventory, we have a responsibility to preserve and repurpose our buildings. Nothing is more sustainable than reutilizing buildings and reducing waste, as seen with the Book Depository building in Corktown. For new buildings, we also have a responsibility to build for the future and make the best choices that we can with the materials at our disposal. Mass Timber is a responsible option and should always be considered. Q: Beyond sustainability, what design or human-scale qualities does mass timber introduce that more conventional materials often don’t? A: Wood brings a natural warmth and biophilic quality that supports wellbeing – lowering stress, improving cognitive function, and creating spaces that feel welcoming and calm. Exposing the structure adds authenticity and makes the architecture legible, helping people feel more grounded in the space. Q: What makes Michigan uniquely positioned to lead in mass timber and low-carbon construction? At the MSU Michigan Mass Timber Update in December, I was able to see the strength of the Michigan mass timber community coming together. The institutional leadership from Michigan State University and their director, Sandra Lupien, is positioning Michigan’s mass timber capabilities on a global level. Connections are being established across the market from – architects, structural engineers, MI EGLE, code officials, business and economic development associations, workforce training leaders to contractors and suppliers. Q: How could mass timber and life cycle thinking influence redevelopment in cities like Detroit, where adaptive reuse and reinvestment are central to the urban story? A: Detroit has led in adaptive reuse for over 25 years, proving that reinvesting in existing buildings delivers cultural, social, economic, and environmental value. Mass timber and lifecycle thinking are the next steps, offering lower carbon pathways as the city continues to grow. To make informed decisions, architects and clients need a full understanding of a material’s life cycle, from extraction and manufacturing to reuse and end of life. This is why circular economy thinking is so critical to future development. At Gensler, our Gensler Product Sustainability (GPS) Standards help guide this process by providing clear, industry-aligned criteria that accelerate the adoption of lower carbon materials in collaboration with the Common Materials Framework. Q: In a region shaped by reinvention, how do you see sustainable materials and measurement tools contributing to the next chapter of Detroit’s built environment? A: Detroit and Michigan have always thrived on reinvention. That same spirit of creativity positions the region to lead in the next wave of sustainable development. Our climate challenges, paired with the natural and industrial resources already here, create an ideal environment for adopting materials and strategies that will help Michigan thrive through future change. The growing investment in next-generation technologies is especially exciting. As industries across the state push toward innovation, there’s real potential for that momentum to drive broader adoption of low carbon materials, mass timber, and performance-based design tools. If we want to attract new residents, businesses, and industries, we need to shape buildings and public spaces that reflect where Detroit is going – healthy, efficient, resilient, and future focused. Q: As sustainability expectations continue to rise, what do you think will separate projects that genuinely reduce impact from those that simply meet minimum standards? Minimum standards are steadily improving as energy codes tighten and reduce allowable energy use, which means operational carbon is no longer the primary differentiator. What will set truly impactful projects apart is a commitment to addressing embodied carbon as well. Conducting Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) early in design gives clients and teams a clear baseline and empowers them to make more informed material choices. Projects that are serious about reducing their overall footprint will also look beyond efficiency to incorporate clean energy—whether by purchasing renewables from their utility or integrating onsite solutions. Michigan is particularly well-suited for ground source heat pumps, with stable underground temperatures that perform reliably through freezing winters and hot summers, and a strong network of engineers and installers who understand the technology. In short, the leaders will be the teams that measure comprehensively, design holistically, and pair low carbon materials

Urban Tech Xchange and Detroit Smart Parking Lab

Now in its fourth year of operation, Urban Tech Xchange (UTX) has become a living laboratory where emerging technology startups can test, refine, and validate smart urban systems in real-world conditions. Launched through a collaboration between Bedrock, Bosch, Cisco, and Kode Labs, UTX builds on the foundation of the Detroit Smart Parking Lab (founded earlier by Bedrock, Ford, MEDC, and Bosch) expanding its scope beyond parking into logistics, energy, building automation, accessibility, and freshwater tech. What differentiates UTX from other technology incubators and accelerators is its emphasis on real-world deployment. Rather than testing concepts in isolation, startups pilot technologies directly within Detroit’s streets, curbsides, buildings, and rooftops, allowing solutions to be measured against real constraints such as emissions reduction, infrastructure utilization, and resident impact. Over the past four years, that approach has helped deploy dozens of pilots and move some into active use. SBN Detroit interviewed Kevin Mull, Bedrock’s Senior Director for Strategic Initiatives, about how Southeast Michigan’s legacy industries are shaping the next era of sustainable urban logistics—and how incremental efficiencies can deliver meaningful environmental gains at city scale. Q: What factors help position Southeast Michigan to rethink how urban logistics can improve daily life in cities like Detroit? A: Southeast Michigan has been designing, building, and deploying mobility solutions for generations. What’s different right now is that we’re at a special moment where the relationships, the talent, and the physical space all align. We have room to test ideas, and we have strong public-private partnerships that allow us to deploy technology. Bedrock’s Detroit Smart Parking Lab (DSPL) and Urban Tech Xchange (UTX) give startups the ability to move beyond theory. Through platforms like the Michigan Mobility Funding Platform, we’ve been able to deploy a million dollars in grants to early-stage companies tackling real logistics and mobility challenges. Over the past four years, several of those pilots have become production-ready solutions now operating across Detroit—from curbside EV charging to streetlight-mounted charging systems. Q: How do wasted miles, underused infrastructure, or inefficient logistics affect urban environments and quality of life? A: Wasted miles translate directly into congestion, emissions, and frustration. Vehicles circling for parking, trucks idling in residential areas, or delivery vehicles double-parking because curb space isn’t managed well—all of that erodes the day-to-day experience of a city. Underutilized infrastructure is another big issue. Curbsides, loading zones, rooftops—these are valuable assets that often aren’t managed intentionally. At Bedrock alone, we process roughly 100,000 parking transactions per month. Every single one of those transactions is an opportunity to reduce friction or create value. We are focusing on solutions that remove friction. One example is IONDynamics, that’s working on automated EV charging. Another is HEVO – a wireless charging solution. Small improvements, repeated thousands of times, add up quickly. Q: How do smarter logistics systems change the way residents experience sustainability day to day? A: Sustainability becomes tangible when it improves daily life. Fewer vehicles circling means cleaner air and quieter streets. Better-managed loading zones mean safer sidewalks. More predictable deliveries mean less congestion during peak hours. One pilot we ran used a small autonomous robot to transport food scraps between restaurants and upcycling locations. Over the course of that project, it diverted more than 2,600 pounds of food waste and eliminated nearly 1,200 pounds of greenhouse gas emissions by replacing traditional vehicle trips. It also avoided the use of about 56 gallons of fuel. Those numbers matter, but what residents notice is the absence of friction—less noise, less traffic, and fewer large vehicles in tight residential spaces. Sustainability works best when it’s embedded into systems people already rely on. Q: How can improved last-mile logistics help reduce unnecessary driving and strengthen neighborhood connectivity? A: The last mile is one of the most important parts of the logistics chain and is often the most inefficient. A lot of energy is going into that space right now because it has outsized impact. Better coordination of curb space, smarter delivery scheduling, and multimodal solutions all reduce the need for unnecessary trips. When people can reliably park, receive deliveries, or access transit without friction, neighborhoods become more functional and connected. We focus on the edges—where parking garages meet transit, where delivery vehicles meet sidewalks, where people move between modes. Improving those interfaces creates meaningful gains without massive infrastructure investments. Q: Many of the technologies supported by UTX reduce congestion and emissions. How do you think about sustainability in this work? A: Sustainability is an outcome of better systems rather than the starting point. When you reduce wasted miles, idle time, and inefficient use of infrastructure, the environmental benefits follow naturally. If we can take miles off the street, shorten dwell times, or make curb space and parking more productive, we reduce emissions without asking people to change their behaviors. Across the Bedrock portfolio, we also think a lot about avoided infrastructure. For example, we’re exploring automated valet parking technology start-ups that aim to allow cars to park closer together and improve garage efficiency by an estimated 20 percent. That can delay—or eliminate—the need to build new parking structures, which has a significant embodied carbon impact. Another example is an automated robot charging solution from Ion Dynamics, which has a charging robot move to the vehicles require charging, which is a dynamic solution that avoids adding costly fixed charging infrastructure. The same logic applies to delivery drones, ground-based robots, and micro-mobility. Moving packages through the air or via small electric vehicles instead of gas-powered trucks reduces fuel consumption and congestion. Q: Where do you see the biggest opportunities for Southeast Michigan cities to improve logistics in ways that benefit both residents and businesses? A: The opportunities are everywhere, but they’re often measured in inches rather than miles. Smarter curbside management. Better coordination between delivery systems and transit hubs. More efficient use of shared infrastructure. Individually, these improvements may seem small. But in the aggregate, they have outsized impact. Through platforms like UTX and DSPL, we’re helping startups test those ideas, refine them, and scale what

Navigating Environmental Compliance

Butzel is one of Michigan’s longest-standing law firms, advising businesses across industries on regulatory compliance, environmental law, and complex commercial matters. As environmental expectations evolve alongside shifting regulatory realities, the firm plays a key role in helping companies navigate both legacy challenges and emerging risks. SBN Detroit interviewed Butzel shareholder Beth Gotthelf to discuss how environmental compliance, sustainability, and innovation are intersecting today — particularly in Southeast Michigan — and what businesses should be paying attention to in the years ahead. Q: From your perspective, what are the most consequential changes shaping how companies approach compliance and sustainability today? A: Many companies still treat compliance and sustainability as separate conversations. Compliance is something they aim for while sustainability is framed as an aspirational goal. Where those two intersect most often is when sustainability also makes business sense. Reducing water use, reusing materials, and improving efficiency often lower costs. Recycling and waste reduction can improve margins. As a result, many organizations are approaching sustainability less as a branding exercise and more as a fiscal and operational strategy. Q: How are businesses navigating the tension between accelerating sustainability goals and increasingly complex regulatory frameworks at the state and federal levels? A: Right now, I don’t see the same level of tension that existed a year or two ago, particularly in Michigan, unless they also have facilities outside of the U.S. or in California. Many companies still believe in climate action and sustainability, but they’re not always using that language domestically given the current federal environment. That said, sustainability reporting is mandated outside the US, with the European Union leading the way for larger firms, and nations like Australia, China, India, and Japan requiring disclosures. Those requirements still apply across all divisions, including U.S. facilities. One area where regulatory complexity is very real is battery recycling, particularly lithium batteries. The regulatory framework in the U.S. makes recycling more difficult than in other countries. That’s an area where we need better alignment to compete in the global market. There is progress happening, but it remains a challenge. Q: Southeast Michigan has a deep industrial legacy alongside growing environmental expectations. What challenges does that history create for remediation and compliance in this region? A: There are many. One challenge, for example, is that materials historically considered “clean fill” may no longer be viewed that way under current standards. The question becomes: do we excavate and remove it all? That creates dust for the area, truck traffic, emissions, road wear, and additional environmental impacts. In some cases, the net environmental benefit is questionable. We also face decisions around highly contaminated sites — whether to cap and manage contamination in place or attempt full remediation to pre-industrial conditions, which can be extremely costly and disruptive. I have simplified the issue but there is a balance between the desire to re-use contaminated sites (brownfield), finding a new productive use, and moving to a ‘greenfield,’ where you do not have to incur the cost, time, and worry of a brownfield. On the compliance side, Southeast Michigan has dense industrial areas adjacent to residential neighborhoods, particularly in places like Southwest Detroit. That proximity creates ongoing tension between maintaining industrial activity and protecting air quality and public health. These are not simple issues, and they require balance rather than absolutes. Q: Are you seeing a shift from reactive environmental compliance to more proactive strategies? A: Yes, overall companies are more proactive than they were decades ago. There’s greater environmental stewardship and awareness. There are better tools to allow for reuse, recycling, lower emissions, fewer chemicals being discharged in wastewater, better management of stormwater, etc. Companies are constantly looking and then implementing those tools. People, whether a resident, employee, or both–want products that last, clean water for swimming and boating, and healthy ecosystems — and they also want manufacturing and economic growth. Balancing those priorities is ongoing but can be done. We can build manufacturing and provide jobs while protecting the environment. Larger companies tend to have more resources to implement sustainability strategies and work with suppliers to raise standards. That said, the last year has been different. Incentives to pursue sustainability have diminished, and in some cases, companies feel penalized for investing in these efforts. That has slowed momentum for some organizations. Q: What role does innovation play in helping companies meet environmental obligations without stalling growth? A: Innovation is essential. It shows up in many forms — energy management software, automation, detection systems, improved chemicals, safer materials, and better protective equipment to name a few. There’s also a real opportunity to expand access to innovation, especially for small and midsize companies. More forums, education, and exposure to tools like energy tracking, water reuse, stormwater management, and greywater systems would help accelerate adoption. Innovation should be encouraged, not siloed. Q: How are climate-related risks influencing environmental decision-making in the Great Lakes region? A: Water quality has become a major concern. The Flint water crisis highlighted how municipal systems directly affect not just residential, but industrial operations. Poor water quality can damage equipment and disrupt production, forcing companies to install additional filtration and safeguards. Flooding is another growing issue. We’re seeing more frequent and severe rain events, impacting facilities across urban and rural areas alike. It is not good when a facility is flooded, potentially allowing chemicals to flow into the environment or causing work to stop. There are a variety of causes of flooding, some related to the drainage system on property, and some off property. Managing flood risk increasingly requires coordination between municipalities and private operators. Extreme weather — snow, wind, heat, flooding — is becoming part of long-term planning. Some larger companies are building redundancy across regions, but many Michigan businesses are smaller and must do the best they can within limited resources. Q: Compared to other regions, what opportunities does Southeast Michigan offer for sustainable redevelopment and clean manufacturing? A: Southeast Michigan has an abundance of industrial sites suitable for adaptive reuse, along with a strong workforce

Sustainability, Sourcing, and the Future of Michigan Manufacturing

Schaeffler is a global automotive and industrial supplier with operations in Southeast Michigan, where it works across the region’s manufacturing and supplier network. As sustainability, decarbonization and supply chain resilience become central to how products are designed and sourced, the region’s role in shaping next-generation manufacturing continues to evolve. SBN Detroit interviewed Courtney Quenneville, who oversees supplier sustainability, to discuss the realities of sustainable sourcing, what decarbonizing a supply chain looks like in practice, and how suppliers in Southeast Michigan can remain competitive amid changing expectations. Q: Southeast Michigan is historically known for automotive manufacturing. As supply chains evolve, what role do you see this region playing in the next generation of sustainable manufacturing and sourcing? A: Southeast Michigan has always been the heart of auto manufacturing, and I see this as a benefit to how we shape the future of sustainable supply chains. Our regional engineering expertise gives us the ability to embed sustainability standards into the earliest phases of design and production. We’re also fortunate to have many local organizations working to raise awareness and build connections across supplier tiers. This mix of awareness and collaboration is what creates the ripple effect that will carry sustainable manufacturing and sourcing into the next generation. Q: What does “decarbonizing a supply chain” actually look like in practice? Where does it begin and what makes it difficult to scale responsibly? A: Decarbonizing a supply chain is being intentional about reduction measures throughout every step, from raw materials being used all the way to delivery methods. It begins with transparency – understanding total emissions across the supply chain and then working directly with suppliers to find practical ways to reduce scope 3 emissions, especially purchased goods and services. The challenge is that not every supplier is at the same point in their sustainability journey; some are already investing in renewable energy or using greener materials, while others are just starting to measure their footprint. It’s important to understand where each supplier partner is at and help them take the next step. Scaling responsibly isn’t about expecting immediate results but building progress together. Q: What are the toughest sustainability challenges suppliers in this region are currently facing? A: Right now, suppliers in this region are facing a lot of uncertainty — tariffs, supply chain shortages, and constant pricing pressures. It’s no surprise that many suppliers feel stuck in crisis or response mode, which makes it harder to focus on long‑term sustainability. At the same time, these challenges highlight why resilience and sustainability go hand in hand. By working closely with suppliers and helping them take practical steps forward, we can show that sustainability isn’t another burden — it’s part of how they stay competitive through all of this change! Q: As more companies move toward science-based targets and emissions reductions, how will this shift affect procurement practices and supplier relationships? A: Just as Schaeffler has done, more companies will commit to science‑based targets, and sustainability will naturally become part of how they source. Procurement will no longer be just about cost and quality. Suppliers will need to be transparent about their emissions in the sourcing process as well as share future reduction levers. This visibility is crucial if we expect to continue reducing impact across the supply chain. The real shift is in relationships. Customers and suppliers will need to work together more than ever to accomplish shared sustainability goals. Once suppliers see how their sustainability efforts open opportunities, they’ll lean in further. Aligning with our suppliers on these initiatives will help determine the strength and future of our partnerships. Q: You’ve helped exceed renewable energy targets in the Americas. What insights have those efforts revealed about what’s working and what’s not? A: It has been encouraging to see the number of suppliers in the region that already have renewable energy plans in place — some are operating at 100% renewable, while others have clear roadmaps to get there. And importantly, they see that we are not the only customer requesting this information, which reinforces for suppliers that renewable energy is now a business expectation, not a side initiative. At the same time, we are learning that cost concerns can slow renewable energy adoption. Some suppliers are weighing the financial impact of renewable energy, which means timelines vary. That’s why our approach is to understand and help suppliers move forward from their current stage. We want progress that is collaborative and realistic. Q: In terms of equity and inclusivity in sourcing, how do supplier diversity and sustainability intersect and why does that matter for economic resilience in Michigan? A: In recent years, more automotive companies have aligned supplier diversity with their Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) initiatives — and in my view, it’s the perfect fit. The ‘social’ pillar is about community development and corporate impact, and nothing strengthens communities more than fueling the local economy. Here in Michigan, we’re fortunate to have thousands of small businesses that are ready to bring innovation and resilience to our supply chains, and investing in these businesses helps build more sustainable communities. With growing pressures to localize production, this is the right moment for Michigan businesses to demonstrate their value. Looking forward, keeping a strong network of local suppliers will be critical, not only for resilience and competitiveness, but also for advancing sustainability across our supply chains and communities. Q: What does it take to ensure traceability and accountability across complex, multi-tier supply chains? A: Traceability is about visibility and accountability is about relationships – and transparency is key for both. It means having the knowledge of your direct suppliers and where materials come from upstream, backed by strong internal tracking and a sustainability team working towards a shared goal. Also, because of the complexity of the multi-tier supply chains, accountability must be handled through collaboration with suppliers – things like industry standards, shared audits, and supplier engagement. Q: Looking ahead five years — what shifts do you expect to see in sustainability requirements and expectations for

Preparing for the AI Energy Era

ThermoVerse is a Detroit-based urban innovation startup founded by engineer and researcher Shantonio Birch. The company’s work centers on advanced thermal energy storage and people-focused building technologies that reduce waste, stabilize indoor environments, and free up electrical capacity. SBN Detroit interviewed Birch about the future of grid resiliency, energy equity, and why Southeast Michigan is positioned to lead in next-generation smart city innovation. Q: What is the impetus behind the work you do? A: ThermoVerse is focused on one of the biggest stability issues we face: how do we allow high-energy users like data centers to coexist in communities without competing for the same energy we need to heat homes and businesses? Our goal is to reduce the largest source of energy consumption in buildings — the HVAC system — so more energy is available at the panel. We want to empower building owners to turn their buildings into value-added assets instead of liabilities. Q: What are the biggest challenges buildings face? A: It all comes down to energy. There are many issues in the built environment, and I think of buildings like the human body — everything is connected. We talk about indoor air quality and comfort, but when you look at economic development, the thing that will get this nation moving is our relationship to energy. Right now, poor power quality is being distributed through the grid and into homes, affecting how our devices and systems function. When you layer on additional demand from advanced manufacturing, EVs, and AI data centers, we’re going to experience more brownouts and blackouts. That’s the biggest challenge buildings are facing: how do we allow this huge economic wave — fueled by AI — without compromising communities? Q: What technologies or approaches will have the greatest impact on reducing energy waste in buildings? A: Anything simple. The biggest barrier for new technology is integration, so solutions have to be straightforward. I believe thermal energy storage is a major opportunity. It will play a huge role in meeting grid-resiliency needs. Renewables like solar are valuable, but they don’t solve the smart-growth challenge we face. We need growth that strengthens the grid rather than stressing it. Q: How does better thermal management translate into healthier or safer living conditions? A: I found my way into this field because I experienced heat stress in my own townhouse apartment during the pandemic while studying at U-M. I was close to heat stroke. We’re seeing more and more cases of heat stress in hospitals and communities now. Better thermal management helps reduce those risks. Beyond the health impact, there’s the economic side. Many people are spending a significant portion of their income on utilities. Improved thermal performance means lower bills, better living conditions, and more resilience as heat waves become more frequent. Q: What role can innovation play in addressing energy inequity — especially in aging housing stock and low-income communities? A: I’ll say this boldly: most existing building technologies were not designed with equity or people in mind. They were built around the question, “How do we cool this space so we can have people here?” At ThermoVerse, we flip that script. We build around the people first. People-centric technologies will play a huge role in reducing energy demand and supporting smart growth so AI and other advancements can coexist with communities instead of overwhelming them. Q: What makes Southeast Michigan a meaningful place to build and test smart-city and energy-efficiency technologies? A: If you look at major cities like Chicago or New York, Detroit stands out. We have the greatest potential for smart-city innovation because our built environment is underdeveloped in certain areas, making the starting point ideal. We can embed smart infrastructure into buildings more easily to enable fluid energy transfer between the grid and the built environment. There’s also a level of openness and willingness here that you don’t always find in cities that are already fully built out. Q: What barriers still slow down the adoption of innovative building technologies, even when they’re proven to reduce waste? A: Integration. That is the barrier for most proven technologies. We also have split incentives in the built environment. Building owners are our customers, but their customers — the tenants — want a better user experience. Then you have utilities, with power-purchase agreements and rate structures that complicate adding new technologies. And finally, the contractors. They’re the ones installing the equipment. If they don’t understand how a new technology fits into existing systems, it won’t be integrated. Heat pumps are a good example — contractor knowledge gaps can slow down adoption, even when the technology is solid. Q: For building owners looking to modernize, where should they focus first to get the biggest energy impact? A: If you’re going to modernize, you have to measure. Establish a baseline. Invest in sensors and meters to understand your energy use down to the unit. You can’t manage what you don’t measure. Once you have visibility, you can start thinking about the ecosystem of technologies that will create the biggest short-term and long-term impact. Ultimately, we need buildings — and neighborhoods — where energy flows bi-directionally between the grid and the built environment. Q: Looking ahead, what do you believe will define the next chapter of energy innovation in Detroit and more broadly? A: Detroit has a deep understanding of how communities and businesses coexist. The next evolution of the built environment here will be people-based — designed around the experience of living and working well. Nationally, we’re at a very interesting moment in energy. For years, the “energy transition” has been politicized, and we’re now looking at it through an economic lens driven by AI. The biggest opportunity ahead is doubling our energy production to meet the demands of AI data centers. The White House recently launched the Genesis Mission — the largest investment in strengthening our national energy reserve to prepare for the new digital era. There’s an enormous opportunity for young people to enter this

Building a Circular Future

In the manufacturing world, sustainability is increasingly defined not just by recycling, but by what kind of recycling. For PolyFlex Products, based in Farmington Hills and part of Nefab Group, the future lies in creating closed-loop systems where materials are reused for equal or higher-value purposes — not simply “downcycled” into lower-grade goods. PolyFlex, which designs and manufactures reusable packaging and material handling solutions for the automotive and industrial sectors, is investing in circularity across its operations. The company’s goal is to ensure that plastics and packaging materials stay in circulation longer, retain value at end-of-life, and contribute to a more resilient supply chain. SBN Detroit interviewed Director of Sustainability Richard Demko, about the shift from downcycling to true circularity, the technical and cultural changes required, and what this evolution could mean for Michigan’s workforce and manufacturing economy. Q: What does “recycling for equivalent or higher use” actually look like in practice — and why is moving away from downcycling so important? A: Circularity, at its core, means manufacturing, recovering, and returning materials at end-of-life back into feedstock form to create something new. It’s about closing the loop — but we have to start with the basics: improving capture rates and diverting more material from landfills. The challenge is that recovery alone doesn’t guarantee success. One of the biggest barriers we face is the lack of demand for recycled feedstock. You can pour your heart into developing a fantastic recycling process, but if there’s no market for that material, the effort falls short. That’s why we need collaborative extended producer responsibility (EPR) systems that stabilize demand and make recycled regrind valuable, instead of punitive frameworks that simply point fingers. No single stakeholder can shoulder all the responsibility for circularity. It’s an ecosystem. Downcycling, meanwhile, is more like an off-ramp — it keeps materials out of landfills for a time but doesn’t truly close the loop. The goal is to return materials to their highest possible value so they can re-enter the economy at an equivalent or higher use. Q: In automotive supply chains, what opportunities do you see for keeping plastics and industrial packaging materials in circulation longer? A: Analyzing packaging fleets at the component level and asking what can be reused, what needs to be redesigned, and what truly has reached end-of-life is a great place to start. Pallets and lids are good examples. Often, those parts can be redeployed across multiple programs if you plan for it upfront. Traditionally, packaging was treated as disposable — once a product launched, everything associated with it ended up scrapped. Now we’re seeing a paradigm shift. Companies are designing for recyclability and reusability from the start. Some are even creating universal packaging platforms that can be shared across product lines. I like to say that carbon has become a kind of currency. When companies invest in reusable packaging, the return isn’t always measured dollar-for-dollar — it’s measured in carbon reduction. Those gains directly support broader sustainability goals, and, in some cases, they even help manufacturers comply with regulations that exempt circular packaging streams from waste classifications. At PolyFlex, we’ve already helped our customers divert several million pounds of plastic from landfills simply by applying design-for-recyclability principles and re-use strategies. It’s a shift toward smarter design — and it’s happening fast. Q: What are the biggest technical challenges in turning used materials back into high-value products — and where is the industry making progress? A: The biggest technical hurdle is consistency. Regrind blends vary depending on their source, and that variability can affect performance. The key is to manage it intentionally — introduce recycled feedstocks in small increments, fine-tune the process, and ramp up gradually. On the positive side, both equipment and operators are getting smarter. We’re seeing tremendous innovation in process technology that allows manufacturers to work with higher recycled content without sacrificing quality or throughput. Q: How do you design a product from the beginning with its second or third life in mind? A: It starts with identifying components that can become standards — like pallet dimensions or lid configurations that can be used across multiple applications. The more we can standardize, the more opportunities we create for re-use. It also requires a macro mindset. Instead of thinking in one product lifecycle, you think in systems. If you’re shipping a component from Detroit to Arizona, ask what can be sent back in that same flow. Can the packaging be refilled, reused, or repurposed? That kind of circular thinking transforms how supply chains operate. Material choice is another major factor. Corrugated packaging might last only a few trips, while plastics designed with the right impact resistance, UV stability, and weather tolerance can circulate for years. It’s about matching the material to its environment and expected lifespan. Q: Are there specific materials where circularity is advancing fastest — and others where it’s still a struggle? A: Rigid plastics — things like pallets, totes, and containers — are advancing the fastest because they’re high volume and easier to process. PET, HDPE, and polypropylene are particularly strong candidates because they can be reprocessed multiple times. Where we still struggle is with single-use, multi-layer packaging — the snack wrappers, films, and laminates that mix materials for barrier protection or freshness. Those layers make recycling extremely difficult. There’s exciting research happening in that space, but large-scale solutions are still developing. Q: What does a more circular plastics industry mean for jobs and skills in Southeast Michigan? A: It means opportunity — but it also means we need education. There isn’t a single university or technical program I know of that teaches recycling as part of its core curriculum. You can find polymer science programs but not recycling operations or circular systems. Training people for this industry is critical. If you lose a skilled recycling technician, you can’t just hire a replacement from a temp agency. It takes months or even years to become proficient. And with plastics recycling, mistakes are costly — something as simple as

Building a People-First Economy in Michigan

People First Economy is a statewide organization working to redefine what success in business looks like—where profitability, community wellbeing, and environmental stewardship go hand in hand. Through education, measurement tools, and peer networks, the nonprofit helps Michigan businesses integrate social and environmental values into everyday operations. SBN Detroit interviewed Carlos Martinez, president of People First Economy, about shifting business mindsets, the growing connection between sustainability and profitability, and why Michigan is uniquely positioned to lead the next economy. Q: Tell me about People First Economy and how it came to be. A: At its core, People First Economy is about building tools and support networks that help shape an economy where people and environmental well-being are essential. We never shy away from the idea of the triple bottom line — businesses can absolutely make a healthy profit while supporting the communities they serve and the environment they depend on. We now serve more than 500 businesses statewide, from early-stage entrepreneurs to established companies. Much of our work centers on education and foundational business practices, but always through the lens of sustainability and inclusion. We started as Local First, which focused on supporting locally owned companies. Over time, our mission expanded to include environmental and social impact — because local economies thrive when businesses are sustainable, equitable, and community-driven. Q: As you work with cohorts, what mindset shifts do you see as companies move toward more inclusive, sustainable practices? A: The biggest shift happens when leaders stop viewing sustainability as an add-on and start seeing it as core to their business strategy. Once companies begin measuring their social and environmental impact, they start acting more proactively. Sustainability becomes part of how they innovate, manage costs, and create value. For larger or more mature businesses, this often leads to a broader cultural shift. They begin evaluating suppliers, employees, and even competitors differently — not as transactions, but as part of a shared ecosystem. That mindset unlocks collaboration and innovation. When companies realize that solving sustainability challenges can actually drive profitability, real transformation begins. Q: What tangible benefits do companies see when they measure their social and environmental impacts? A: One of the biggest is employee engagement. When people see that their company is making a positive difference, they feel connected to something larger than their job. We also see efficiency gains, cost savings from smarter resource management, and stronger brand loyalty. But there’s another layer — storytelling. When businesses can measure their impact, they can share those results in powerful ways. It becomes part of their identity. For example, Walker-Miller Energy Services and Cascade Engineering in Michigan both demonstrate how sustainability and inclusion strengthen brand reputation and build employee pride. More companies are now including impact reporting in their marketing or RFP materials because it helps them stand out. When you can prove your values, you open doors to new opportunities. A Harvard study recently found that purpose-driven companies embedding sustainability into their culture outperform the market nearly tenfold over two decades. That connection between purpose and profit is real. The business impact strategies create lasting value when they’re grounded in a deep understanding of a company’s financial metrics. Q: How do you encourage businesses to think about long-term value rather than short-term profit? A: This is always an evolving conversation, especially in challenging economic times. The key is understanding that we’re all interconnected. A diverse, resilient business community helps protect against national downturns and future disruptions. Companies that invest early in sustainable, innovative practices often find themselves better positioned when the market shifts. Patagonia is a good example — years ago, they were experimenting with regenerative agriculture, which at the time seemed niche. Today, it’s a standard for sustainable production. When you build trust, brand loyalty, and local supply chains, it creates stability. Over the long term, that stability translates to profitability. Q: Detroit and Michigan have a rich manufacturing legacy. How is the people-first model reshaping the regional narrative around business and jobs? A: Detroit is unique because it already has a strong foundation of community-based leadership. Other states look to Detroit as a model for what’s possible when innovation and inclusion go hand in hand. We’re still early in the process of embedding this mindset more broadly, but the momentum is there. When we opened applications for our latest sustainability cohort, we had more than 50 applicants for just 20 spots — which tells us there’s real appetite for this work. Our broader goals include connecting early-stage businesses with those further along in their sustainability journey — through tools, mentorship, and experiences like conferences where they can see what’s possible. It’s about building a community of practice. The more we connect those dots, the stronger our local economy becomes. Q: If you were advising a mid-size company in Detroit today, what’s the best first step toward embedding people-first practices? A: Start by understanding where you are. We always recommend beginning with a sustainability or impact assessment. Then pick one or two achievable goals, such as improving employee benefits, reducing waste, or sourcing locally. Progress happens through small, transparent steps, not perfection. I’m an entrepreneur myself, and when I first took an assessment myself, I panicked — but that’s the point. It’s about identifying opportunities for improvement, not judgment. Once you see where you can make a change, momentum builds. It’s a marathon, not a sprint. Q: Where do you see the biggest growth opportunities for Michigan businesses in the next five years? A: Growth lies at the intersection of sustainability, equity, and innovation. The clean energy transition alone represents a multi-trillion-dollar opportunity. There’s also growing potential in circular manufacturing and workforce development and worker-owned cooperatives. We need to make sure those opportunities are equitable. Detroit has a majority Black population, and Michigan has several key regions with strong, diverse, but underserved communities. As major investments flow into green energy and infrastructure, it’s vital that local entrepreneurs and workers share in that growth. This is still a foundational phase. Some of the biggest