- Kim Kisner

- Community

- 01/29/2026

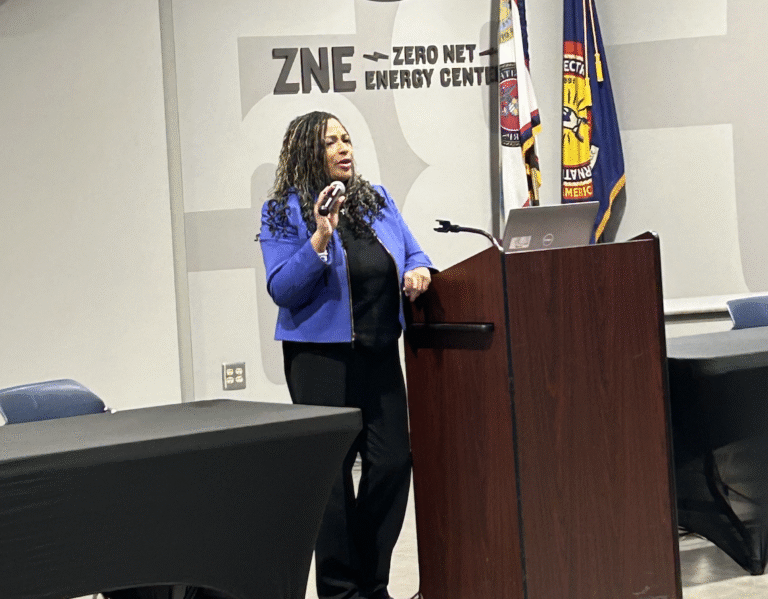

A Talk With the State’s First Environmental Justice Public Advocate

Regina Strong serves as Michigan’s first Environmental Justice Public Advocate, leading the state’s Office of the Environmental Justice Public Advocate. Her role focuses on addressing environmental justice concerns raised by communities, helping residents navigate environmental systems, and working across state agencies to improve equity in environmental decision-making.

SBN Detroit interviewed Strong about the challenges communities are facing across Michigan and what environmental justice work looks like in practice.

Q: As Environmental Justice Public Advocate, what does your work look like day to day?

A: There really is no typical day. This role was created to address environmental justice concerns and complaints, to advocate for equity, and to help communities navigate systems that can feel opaque or inaccessible. That can mean many things.

On a given day, I might be working on our Environmental Justice Screening Tool as we migrate it to a new platform, meeting with one of our 43 grantees across the state, or sitting down with other state departments or divisions within EGLE, where my office is housed. Other days are spent directly with community members – listening to concerns, helping them understand what levers exist, and figuring out how to move forward.

The work ebbs and flows depending on what’s happening in communities. Over the past seven years, we’ve seen some issues emerge seasonally, in response to new development, extreme weather, or long-standing infrastructure issues. Ultimately, my work is deeply relational and constantly evolving.

Q: What are the most pressing environmental justice issues you’re hearing across Michigan and how do they differ between urban, suburban, and rural communities?

A: There’s actually a lot of overlap across geographies. Whether people live in dense urban neighborhoods, suburban communities, or rural areas, we consistently hear concerns about water – lead service lines, contaminated wells in rural areas, and flooding. Air quality is another major issue, especially near industrial corridors or transportation infrastructure.

In more densely populated areas, concerns often cluster around industry, waste facilities, landfills, and cumulative air pollution. In rural areas, it may be wells, septic systems, or access to clean drinking water. Across all regions, energy burden comes up frequently, particularly during winter months, when households are forced to spend a disproportionate share of income on utilities.

Climate change is amplifying many of these issues. Flooding, power outages, and extreme weather events are becoming more common, and their impacts are not evenly distributed. The underlying issues may differ by location, but the throughline is vulnerability tied to infrastructure, income, and exposure.

Q: What are the hardest gaps to close when translating community concerns into action?

A: One of the biggest challenges is that environmental justice issues rarely fall under a single authority. A concern may involve state permitting, local zoning, county health departments, and federal regulations all at once. Our office often helps communities navigate those layers.

From an environmental justice perspective, equitable access to decision-making is critical. We work to ensure voices are heard, especially in communities that have historically been underserved. We do a lot of resilience planning in – for example – the 48217 ZIP code (Southwest Detroit) in the heart of a very dense industrial corridor. We also work with communities near hazardous waste facilities and communities with drinking water concerns.

Many of these challenges have deep historical roots. Our role is often about helping communities access resources, understand processes, and advocate effectively while acknowledging that solutions are rarely immediate, yet possible.

Q: To that end, how does history complicate environmental justice work today?

A: History matters a great deal. Many environmental regulations around air and water are set at the federal level and applied category by category. Communities, however, experience impacts cumulatively – air, water, land use, and health intersecting in daily life.

That mismatch creates tension. Residents want holistic solutions, but regulatory frameworks don’t always account for cumulative impacts. Before the Clean Air Act and Safe Drinking Water Act, people lived near industrial facilities for decades – and still do. Laws have improved, but legacy exposure and infrastructure decisions remain.

Balancing regulatory constraints with community realities is one of the most complex aspects of this work.

Q: What structural or systemic barriers are hardest to change?

A: Policy is often written within narrow frameworks that don’t always center people’s lived experiences. That’s a persistent barrier. Another is data – how it’s collected, interpreted, and applied.

MI EJ Screen, the state’s environmental justice screening tool is designed to help address that gap. It looks at environmental conditions, demographics, and health indicators together, creating a shared reference point for communities, government, and industry. The first version was launched in 2024, and expanding its usability is a priority because shared data helps align conversations and advocacy.

Understanding how existing laws interact and where they fall short remains both a challenge and an opportunity.

Q: How has your background in clean energy advocacy and community development shaped your approach?

A: Where you live often determines the challenges you face. Working in community development and later in clean energy made that clear. Lower-income communities and communities of color are more likely to experience environmental burdens, often due to proximity to industry or aging infrastructure.

That perspective informs everything I do. Some issues can be addressed through regulation, but others require working directly with communities to improve daily quality of life. Our Environmental Justice Impact Grant Program is one example – 43 grants statewide, including many in Detroit, supporting grassroots organizations, schools and communities addressing local concerns.

This office sits outside of regulatory enforcement, which allows us to take a broader, more human-centered view.

Q: How do you think about progress for residents living with impacts right now?

A: Progress can look small but be very meaningful. Having a dedicated office focused on environmental justice is progress. Having tools that didn’t exist before is progress.

If progress means a senior is no longer dealing with basement flooding because they received support for a sump pump, that matters. We have to focus on both micro-level quality-of-life improvements and longer-term policy change at the same time.

Q: Looking ahead, what work feels most critical?

A: Preparing for what we know will intensify. Flooding, climate impacts, air and water challenges. Removing lead service lines, mitigating climate-related disparities, and ensuring equitable access to resources will define the next phase of this work.

Equally important is letting communities speak for themselves. Through the Michigan Advisory Council on Environmental Justice (MACEJ), which is made up of residents in communities with environmental justice concerns, community organizations, business, labor, tribal representation, local governments and academic leaders that have presence and roots in the communities we work in – we hear directly from advocates with lived experience and those who are actively working to have impact in communities. That partnership between government and community is essential.

Environmental justice isn’t about quick fixes. It’s about building systems that recognize history, address present realities, and create equitable conditions today and into the future.

Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on sustainable business practices in and around Detroit.

Kim Kisner

- All

- Business

- Community

- Education

- Events

Detroit-based nonprofit Elevate focuses on the intersection of energy equity, housing stability, and workforce development. Through community partnerships and programs that connect residents with energy-efficiency upgrades, education, and job-training opportunities, the organization works to strengthen neighborhoods while helping families reduce costs and improve living conditions. SBN Detroit interviewed Shawna Forbes Henry, Director of Community Programs at Elevate, about the broader implications of energy access, the structural barriers communities...

The Green Business Lab, founded in 2002 by Samantha Svoboda, aims to help organizations strengthen decision-making about sustainability through immersive business simulations and strategic advisory services. Working with leadership teams across industries, the Lab creates structured environments where executives can explore how environmental, operational, and market forces intersect with core business strategy. Over more than two decades, the Green Business Lab has worked with companies toward moving sustainability...

Unique Monique Scented Candles, a Detroit-based business founded by Monique Bounds., aims to produce candles and household products with clean ingredients and local supply chains. What began as a personal hobby during college has evolved into a full-time venture producing coconut oil and soy-based candles made with essential oils and locally sourced materials. SBN Detroit interviewed Bounds about launching a sustainable product line, sourcing challenges in Michigan, and...