- Kim Kisner

- Business

- 11/06/2024

Veridian at County Farm is Targeted to be Among the First U.S. Mixed-Income, Net-Zero U.S. Communities

THRIVE Collaborative is an Ann Arbor-based real estate development, design, building, and consulting firm dedicated to creating life-enhancing, grid-interactive buildings that harvest their own energy and water, create zero waste, and are beautiful and restorative.

Its current project – Veridian at County Farm in Ann Arbor – is a 100% electric development, powered by solar with no gas lines or combustion appliances. It is targeted to be one of the nation’s first mixed-income net zero energy communities.

SBN Detroit interviewed Matt Grocoff, THRIVE Collaborative founder and lead on the Veridian project, to find out more.

Q: How do you approach creating buildings that harvest their energy and water and create zero waste, and how long have you been doing this work?

A: Thrive Collaborative approaches sustainable development by aiming to create buildings and communities that align with what is necessary for the future. Our flagship project, Veridian, is a model for addressing pressing climate challenges. When we started Veridian in 2016, we were guided by the goals of the Paris Agreement, which sets a target of keeping global temperature increases below 1.5 degrees Celsius. This means eliminating fossil fuels and using only renewable energy to power buildings.

I see Veridian as an act of optimism. It is a 100% all-electric community, with no gas or fossil fuels. It’s powered entirely by on-site renewable energy, including solar panels, battery storage, and geothermal systems. Every home in the development produces more energy than it consumes, ensuring it is not only sustainable but capable of energy storage for future use. The idea is to show that what we need to do for the planet can also create a beautiful and socially just way of living.

Q: In your experience, what are the biggest challenges in integrating sustainable practices into real estate development in Southeast Michigan?

A: One of the biggest challenges we face is that there is no existing template for what we are trying to accomplish. The science of sustainability is clear, but the regulatory framework, building codes, and conventional construction practices in the U.S. don’t match what we are trying to achieve.

Veridian uses a specific permeable road surface called Ecoraster. This is an eco-friendly, flexible, porous paver made from 10% post-consumer and post-industrial recycled plastics. However, the material was initially rejected by the city. We had to prove it met the necessary standards, which took nine months to do.

This is one of dozens – maybe hundreds of examples of outdated building codes and policies that just don’t align to support the materials and practices we are employing.

There are also challenges related to training contractors and tradespeople in new, sustainable methods.

Q: How have you navigated these challenges?

A: The key is to approach it knowing that sustainable development is both necessary and possible. There are always people who say, “That’s not how construction is done,” but that resistance creates an opportunity for innovation.

Q: What role does Veridian play in the broader sustainability movement in Southeast Michigan, and what are your long-term goals for this project?

A: At a micro level, Veridian Farms is about creating a model neighborhood that implements the necessary solutions for sustainability. The project serves as a case study for what’s possible when we fully embrace renewable energy, energy efficiency, and zero-waste practices.

At a macro level, the goal is to demonstrate that these methods can and should be replicated across Southeast Michigan and beyond. The science is telling us that we need to cut global carbon emissions in half by 2030 to prevent the worst impacts of climate change. By showing that this level of sustainability is possible today, we hope to inspire policymakers, developers, and financial systems to support and scale these efforts.

Q: What are the economic implications of building sustainable communities like Veridian?

A: There’s often a misconception that building sustainably is prohibitively expensive, but that’s not the case when you take a holistic view. While technologies like geothermal heating and certain types of appliances might cost more upfront, they pay off over time. Solar panels, for example, lock in energy costs for 30 years, which is far more economical than relying on fossil fuels, whose prices fluctuate.

When we look at costs holistically — factoring in the environmental impact of conventional practices — sustainable building becomes the more affordable option. We must rethink what “cost” means, not just in terms of the price of materials but in terms of the long-term health of the planet and the people who live in these homes.

Q: What is the timeline for Veridian?

A: We proposed the project in 2016. It took a couple of years to get approved. We are almost to year nine and we have our first residents living there now. The renewable energy systems are up and running and every home is producing more energy than it uses. Homes are heated and cooled with energy provided by the sun. Instead of storm drains, we have bioswales and butterfly gardens and birds and plants. We engineer using plants and pipes, but we use natural systems to operate more elegantly than the conventional expensive, and unsustainable storm drain systems.

By the end of the year, we’ll have all residents moved into our first sequence, which is 21 single-family homes. By early next year, we’ll have another ten two-bedroom lofts occupied.

Q: What are some of the lessons you’ve learned from past projects that are helping guide future developments?

A: All innovative projects are learning opportunities. One major lesson is the need for a significant shift in the American construction industry. Compared to Europe, where sustainable building practices are more advanced and efficient, the U.S. lags in terms of both financial structure and the materials used. We also need to address the utter lack of diversity in the trades—something Europe has done more effectively.

We’ve also learned that collaboration is critical. Whether it’s working with local governments to navigate building codes or partnering with vendors to source sustainable materials, the process requires cooperation across multiple sectors.

Q: Looking ahead, what do you see as the future of sustainable development in Southeast Michigan?

A: I’m hopeful that what we are doing at Veridian will inspire others to follow. We’re already seeing developers and policymakers from across the country reach out to learn how they can implement similar systems. The goal is for projects like Veridian to stop being seen as “eco-friendly exceptions” and become the standard for new developments.

I’m hopeful that policy, financial, and mortgage systems will eventually catch up, making it easier to build these communities on a larger scale. We need to prove that this kind of development is not only possible but necessary for the future of our planet and society.

Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on sustainable business practices in and around Detroit.

Kim Kisner

- All

- Business

- Community

- Education

- Events

Unique Monique Scented Candles, a Detroit-based business founded by Monique Bounds., aims to produce candles and household products with clean ingredients and local supply chains. What began as a personal hobby during college has evolved into a full-time venture producing coconut oil and soy-based candles made with essential oils and locally sourced materials. SBN Detroit interviewed Bounds about launching a sustainable product line, sourcing challenges in Michigan, and...

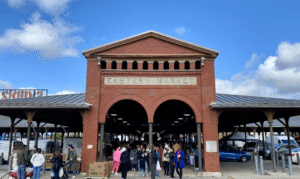

Eastern Market Partnership, in collaboration with the City of Detroit’s Office of Sustainability Urban Agriculture Division, has announced $240,000 in grant funding to support Detroit-based farmers and farmer collectives. The grants will advance food access, climate education, sustainable land use, and economic opportunity, with priority given to Black- and Indigenous-led farms, youth-led initiatives, and projects rooted in historically disinvested neighborhoods. The recipients – ranging from cooperatives and community...

Citizen Robotics is a Detroit-based nonprofit that advances the use of robotics and digital manufacturing in residential construction, focusing on improving productivity, sustainability, and long-term affordability. Best known for its early work in 3D-printed housing, it explores how alternative construction methods and new financial models can reduce material waste, lower lifetime operating costs, and enhance the resilience of homes. SBN Detroit interviewed Tom Woodman, founder and president of...